THE AMBASSADOR

By Sam Merwin, Jr.

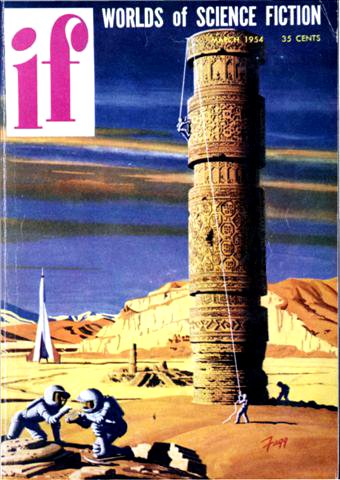

Illustrated by Kelly Freas

[Transcriber Note: This etext was produced from IF Worlds of ScienceFiction March 1954. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence thatthe U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Zalen Lindsay stood on the rostrum in the huge new United Worldsauditorium on the shore of Lake Pontchartrain and looked out at an oceanof eye-glasses. Individually they ranged in hue from the rose-tintedspectacles of the Americans to the dark brown of the Soviet bloc. Theirshapes and adornments were legion: round, harlequin, diamond, rhomboid,octagonal, square, oval; rimless, gem-studded, horn-rimmed,floral-rimmed, rimmed in the cases of some of the lady representativeswith immense artificial eyelashes.

The total effect, to Lindsay, was of looking at an immense page ofprinted matter composed entirely of punctuation marks. Unspectacled, hefelt like a man from Mars. He was a man from Mars—first MartianAmbassador Plenipotentiary to the Second United Worlds Congress.

He wished he could see some of the eyes behind the protective goggles,for he knew he was making them blink.

He glanced down at the teleprompter in front of him—purely to addeffect to a pause, for he had memorized his speech and was delivering itwithout notes. On it was printed: HEY, BOSS—DON'T FORGET YOU GOT ADINNER DATE WITH THE SEC-GEN TONIGHT.

Lindsay suppressed a smile and said, "In conclusion, I am qualified bythe governors of Mars to promise that if we receive another shipment ofBritish hunting boots we shall destroy them immediately uponunloading—and refuse categorically to ship further beryllium to Earth.

"On Mars we raise animals for food, not for sport—we consider humanbeings as the only fit athletic competition for other humans—and we seesmall purpose in expending our resources mining beryllium or othermetals for payment that is worse than worthless. In short, we will notbe a dumping ground for Earth's surplus goods. I thank you."

The faint echo of his words came back to him as he stepped down from therostrum and walked slowly to his solitary seat in the otherwise emptysection allotted to representatives of alien planets. Otherwise therewas no sound in the huge assemblage.

He felt a tremendous lift of tension, the joyousness of a man who hassatisfied a lifelong yearning to toss a brick through a plate-glasswindow and knows he will be arrested for it and doesn't care.

There was going to be hell to pay—and Lindsay was honestly lookingforward to it. While Secretary General Carlo Bergozza, his dark-greenspectacles resembling parenthesis marks on either side of his thin eaglebeak, went through the motions of adjourning the Congress forforty-eight hours, Lindsay considered his mission and its purpose.

Earth—a planet whose age-old feuds had been largely vitiated by theincreasing rule of computer-judgment—and Mars, the one settled alienplanet on which no computer had ever been built, were driftingdangerously apart.

It was, Lindsay thought with a trace of grimness, the same ancient storyof the mother country and