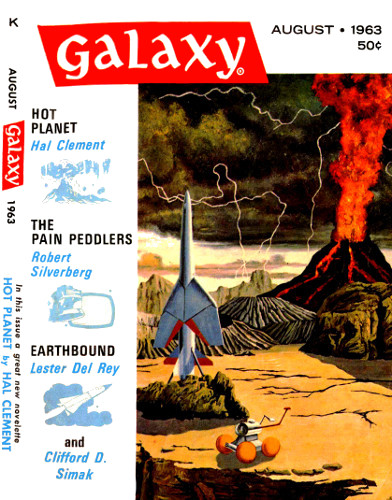

HOT PLANET

By HAL CLEMENT

Illustrated by FINLAY

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Galaxy Magazine August 1963.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Mercury had no atmosphere—everyone knew

that. Why was it developing one now?

I

The wind which had nearly turned the Albireo's landing into adisaster instead of a mathematical exercise was still playing tunesabout the fins and landing legs as Schlossberg made his way down toDeck Five.

The noise didn't bother him particularly, though the endless seismictremors made him dislike the ladders. But just now he was able toignore both. He was curious—though not hopeful.

"Is there anything at all obvious on the last sets of tapes, Joe?"

Mardikian, the geophysicist, shrugged. "Just what you'd expect ... ona planet which has at least one quake in each fifty-mile-square areaevery five minutes. You know yourself we had a nice seismic program setup, but when we touched down we found we couldn't carry it out. We'vedone our best with the natural tremors—incidentally stealing most ofthe record tapes the other projects would have used. We have a lot ofnice information for the computers back home; but it will take all ofthem to make any sense out of it."

Schlossberg nodded; the words had not been necessary. His astronomicalprogram had been one of those sabotaged by the transfer of tapes to theseismic survey.

"I just hoped," he said. "We each have an idea why Mercury developedan atmosphere during the last few decades, but I guess the high schoolkids on Earth will know whether it's right before we do. I'm resignedto living in a chess-type universe—few and simple rules, but infinitecombinations of them. But it would be nice to know an answer sometime."

"So it would. As a matter of fact, I need to know a couple right now.From you. How close to finished are the other programs—or what's leftof them?"

"I'm all set," replied Schlossberg. "I have a couple of instrumentsstill monitoring the sun just in case, but everything in the revisedprogram is on tape."

"Good. Tom, any use asking you?"

The biologist grimaced. "I've been shown two hundred and sixteendifferent samples of rock and dust. I have examined in detail twelvecrystal growths which looked vaguely like vegetation. Nothing was aliveor contained living things by any standards I could conscientiouslyset."

Mardikian's gesture might have meant sympathy.

"Camille?"

"I may as well stop now as any time. I'll never be through. Tape didn'tmake much difference to me, but I wish I knew what weight of specimensI could take home."

"Eileen?" Mardikian's glance at the stratigrapher took the place of theactual question.

"Cam speaks for me, except that I could have used any more tape youcould have spared. What I have is gone."

"All right, that leaves me, the tape-thief. The last spools are in theseismographs now, and will start running out in seventeen hours. Thetractors will start out on their last rounds in sixteen, and should beback in roughly a week. Will, does that give you enough to figure theweights we rockhounds can have on the return trip?"

The Albireo's captain nodded. "Close enough. There really hasn't beenmuch question since it became evident we'd find nothing for the masstanks here. I'll have a really precise check in an hour, but I cantell right now that you have abou