SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION.

UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM.

MANCALA, THE NATIONAL GAME OF AFRICA.

BY

STEWART CULIN,

Director of the Museum of Archæology and Palæontology,

University of Pennsylvania.

From the Report of the U. S. National Museum for 1894, pages 595-607,with plates 1-5 and figures 1-15.

WASHINGTON:

GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE.

1896.

MANCALA, THE NATIONAL GAME OF AFRICA.

BY

STEWART CULIN,

Director of the Museum of Archæology and Palæontology,

University of Pennsylvania.

MANCALA, THE NATIONAL GAME OF AFRICA. [1]

By Stewart Culin,

Director of the Museum of Archæology and Palæontology, University of Pennsylvania.

[1]Read before the Oriental Club of Philadelphia, May 10, 1894.

The comparative study of games is one that promises an importantcontribution to the history of culture. The questions involved in theirdiffusion over the earth are among the vital ones that confound theethnologist. Their origins are lost in the unwritten history of the childhoodof man. Mancala is a game that is remarkable for its peculiardistribution, which seems to mark the limits of Arab culture, and whichhas just penetrated our own continent after having served for ages todivert the inhabitants of nearly half the inhabited area of the globe.

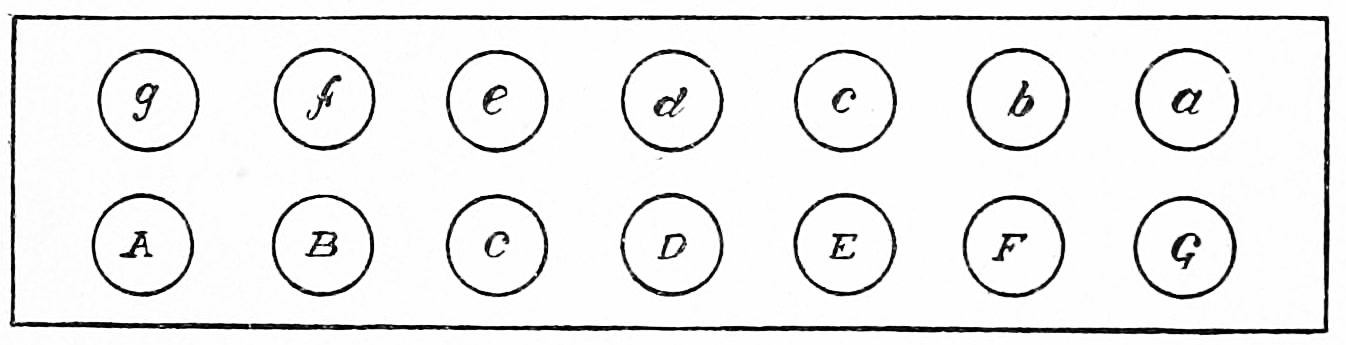

Fig. 1.

MANCALA.

From a figure by Lane.

The visitor to the little Syrian colony in Washington street in NewYork City will often find two men intent upon this game. They callit Mancala. The implements are a board with two rows of cup-shapeddepressions and a handful or so of pebbles or shells, which they transferfrom one hole to another with much rapidity. A lad from Damascusdescribed to methe methodsof play. Thereare two principalways, whichdepend uponthe manner inwhich the piecesare distributedat the commencement of the game. Two persons always engage, andninety-eight cowrie shells (wada) or pebbles (hajdar) are used. Onegame is called La’b madjnuni, or the “Crazy game.” The players seatthemselves with the board placed lengthwise between them. One distributesthe pieces in the fourteen holes, called bute, “houses,” not lessthan two being placed in one hole. This player then takes all thepieces from the hole at the right of his row, fig. 1, G, called el ras, “thehead,” and drops them one at a time into the holes on the opposite side,commencing with a, b, c, and so on. If any r