THE

LONDON PLEASURE GARDENS

OF

THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

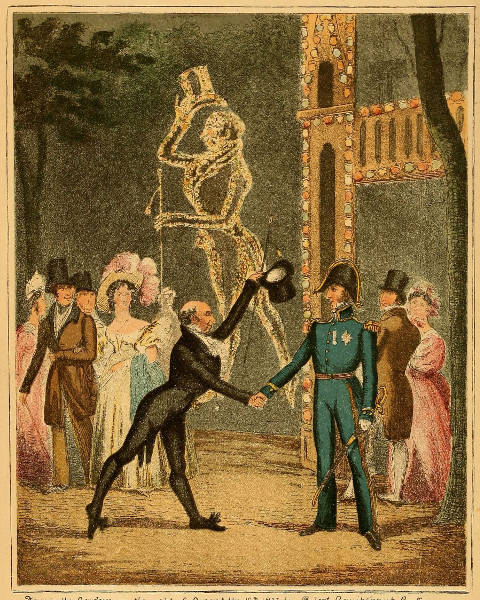

Drawn in the Gardens, on the night of August the19th 1833, by Robert Cruikshank Esqr.——

C.H. SIMPSON, ESQR. M.C.R.G.V.

For upwards of 36 Years,—with a distant view of his ColossalLikeness in Variegated Lamps.

To C. H. Simpson, Esqr. M.C. of the Royal Gardens Vauxhall,—thisPrint, taken in the Sixty Third year of his age, on the Night of hisbenefit is, by express permission, most respectfully dedicated by hisobliged and humble Servant,—the Publisher.

London. Published by W. Hidd. 14. Chandos St.t West Strand, August20.th 1833.

THE LONDON

PLEASURE GARDENS

OF

THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

BY

WARWICK WROTH, F.S.A.

OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM

ASSISTED BY

ARTHUR EDGAR WROTH

WITH SIXTY-TWO ILLUSTRATIONS

London

MACMILLAN AND CO., Ltd.

NEW YORK: THE MACMILLAN CO.

1896

The Right of Translation and Reproduction is Reserved

“A great deal of company, and the weather and garden pleasantand it is very cheap and pleasant going thither.... But to hearthe nightingale and the birds, and here fiddles and there aharp, and here a Jew’s trump, and here laughing and there finepeople walking is mighty divertising.”—Samuel Pepys.

[v]

PREFACE

In the following pages an attempt has been made to write, for the firsttime, a history of the London pleasure gardens of the last century.Scattered notices of these gardens are to be found in many histories ofthe London parishes and in other less accessible sources, and merelyto collect this information in a single volume would not, perhaps,have been a useless task. It is one, however, that could not havebeen undertaken with much satisfaction unless there was a prospect ofmaking some substantial additions—especially in the case of the lessknown gardens—to the accounts already existing. A good deal of suchnew material it has here been possible to furnish from a collection ofnewspapers, prints, songs, &c., that I have been forming for severalyears to illustrate the history of the London Gardens.[1]

The information available in the writings of such laborioustopographers as Wilkinson, Pinks, and Nelson is, of course,indispensable, and has not been here[vi] neglected; yet even in thetreatment of old material there seemed room for improvement, atleast in the matter of lucidity of arrangement and chronologicaldefiniteness. For, if the older histories of the London parishes havea fault, it is, perhaps, that, owing to their authors’ anxiety to omitnothing, they often read more like materials for history thanhistory itself. Thus, we find advertisements and