LITTLE BOY

BY HARRY NEAL

There are times when the animal in Mankind

savagely asserts itself. Even children become

snarling little beasts. Fortunately, however,

in childhood laughter is not buried deep.

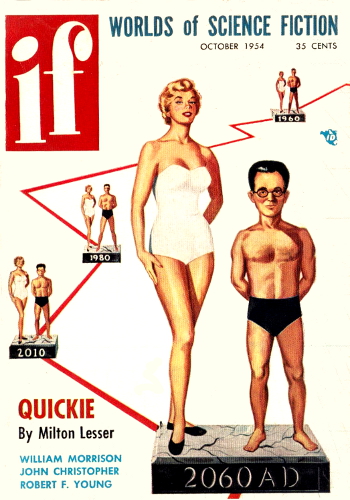

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Worlds of If Science Fiction, October 1954.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

He dropped over the stone wall and flattened to the ground. He lookedwarily about him like a young wolf, head down, eyes up. His name wasSteven—but he'd forgotten that. His face was a sunburned, bitter,filthy eleven-year-old face—tight lips, lean cheeks, sharp blueeyes with startlingly clear whites. His clothes were rags—a pair ofcorduroy trousers without any knees; a man's white shirt, far too bigfor him, full of holes, stained, reeking with sweat; a pair of dirtybrown sneakers.

He lay, knife in hand, and waited to see if anyone had seen him comingover the wall or heard his almost soundless landing on the weedgrowndirt.

Above and behind him was the grey stone wall that ran along CentralPark West all the way from Columbus Circle to the edge of Harlem.He had jumped over just north of 72nd Street. Here the park wasconsiderably below street level—the wall was about three feet high onthe sidewalk side and about nine feet high on the park side. From wherehe lay at the foot of the wall only the jagged, leaning tops of theshattered apartment buildings across the street were visible. Like theteeth of a skull's smile they caught the late afternoon sunlight thatdrifted across the park.

For five minutes Steven had knelt motionless on one of the cementbenches on the other side of the wall, just the top of his head and hiseyes protruding over the top. He had seen no one moving in the park.Every few seconds he had looked up and down the street behind him tomake sure that no one was sneaking up on him that way. Once he hadseen a man dart out halfway across the street, then wheel and vanishback into the rubble where one whole side of an apartment house hadcollapsed into 68th Street.

Steven knew the reason for that. A dozen blocks down the street, fromaround Columbus Circle, had come the distant hollow racket of a pack ofdogs.

Then he had jumped over the wall—partly because the dogs might headthis way, partly because the best time to move was when you couldn'tsee anyone else. After all, you could never be sure that no one wasseeing you. You just moved, and then you waited to see if anythinghappened. If someone came at you, you fought. Or ran, if the otherlooked too dangerous.

No one came at him this time. Only a few days ago he'd come into thepark and two men had been hidden in the bushes a few yards from thewall. They'd been lying very still, and had covered themselves withleaves, so he hadn't seen them; and they'd been looking the other way,waiting for someone to come along one of the paths or through thetrees, so they hadn't seen him looking over the wall.

The instant he'd landed, they were up and chasing him, yelling that ifhe'd drop his knife and any food he had they'd let him go. He droppedthe knife, because he had others at home—and when they stopped to pawfor it in the leaves, he got away.

Now he got into a crouching position, very slowly. His nostrils dilatedas he sniffed the breeze. Sometimes you knew men were near by theirsmell—the ones who didn't stand outside when it rained and scrub thesmell off them.

He smelled nothin