WHAT DO YOU READ?

By Boyd Ellanby

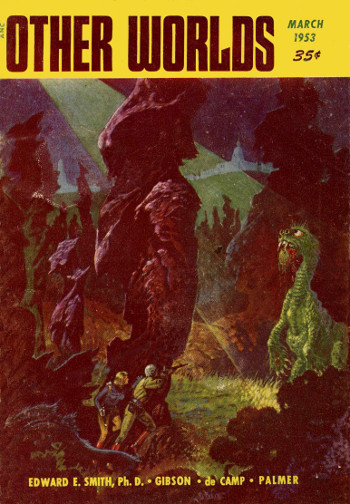

Illustrated by Malcolm Smith

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from Other Worlds March

1953. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S.

copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Writers have long dreamed of a plot machine, but the machines inScript-Lab did much more than plot the story—they wrote it. Why botherwith human writers when the machines did the job so much faster andbetter?

Herbert would have preferred the seclusion of a coptor-taxi, but heknew he could not afford it. The Bureau paid its writers adequately,but not enough to make them comfortable in taxis. In front of hisapartment house, he took the escalator to the Airway. It must have beenpleasant, he thought as he stepped onto the moving sidewalk, to be awriter in the days when they were permitted to receive royalties and,presumably, to afford taxi fare.

On the rare occasions when he was forced to travel in the city, heusually tried to insulate himself from the Airway crowds by trying toconstruct new plots for his fiction. In his younger days, of course, hehad occupied the time in reading the classics, but lately, so great wasthe confusion of the city, he preferred to close his eyes, and try todevise a reverse twist for one of his old stories.

Today, he found it harder than usual to concentrate. The Airway wascrowded, and he had never heard the people so noisy. Up ahead half ablock, there was a sharp scream. Herbert opened his eyes and peeredahead to see what had happened. Someone had been pushed through therailing of the Airway, and as his section rolled on and passed, hecould see lying on the pavement below the body of a young cripple, hishands still holding a broken crutch.

Herbert shuddered. He felt sick, and closed his eyes again.

"Wonder how that happened?" said the man in front of him.

"He probably got in the way," said a girl, callously.

The man ahead made no comment, and Herbert dismissed his ownpuzzlement. Could he make a plot out of this incident of the crippledboy? he wondered.

He shifted to the slower track, descended the escalator, and steppedonto the street across from the Bureau of Public Entertainment. He hadto wait a moment, for an ambulance was clanging down the street; thenhe crossed to the stone-faced building.

As he rode up the elevator, he wondered again why John had ordered himto come to lunch. He realized that he was no longer a young man, but hecertainly did not feel ready to be pensioned. And in the last year hehad actually written more fiction than in any other year of his life.Very little of it had been used, for some reason, but story for storyhe thought it matched any of his previous output.

Ludwig received him with little ceremony. "Sit down, Herbert. It wasgood of you to come. Miss Dodson," he called through the intercom,"this is strictly off the air. Nothing is to be recorded. Is thatclear?"

"Well, John," said Carre. "You're looking harassed, if I may sayso. Are they working you too hard? Or are you just faced with theunpleasant job of firing an old friend? I realize, of course, that AFEaren't using much of my stuff just now."

Ludwig smiled unhappily and shook his head. "I'm not planning to fireyou, Herbert. But you know, of course, that you're in the same boatwith the other Writers, and that boat is in choppy waters. Frankly,I'm not very happy about the situation. The five-year experimentalperiod is coming to an end. This Bureau has the job of providi