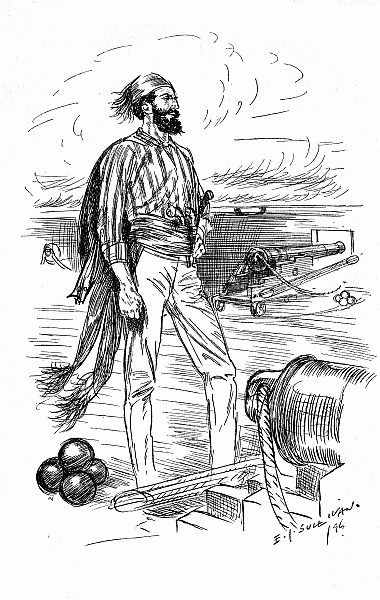

THE PIRATE

AND

THE THREE CUTTERS

THE PIRATE

AND

THE THREE CUTTERS

BY

CAPTAIN MARRYAT

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY EDMUND J. SULLIVAN

AND AN INTRODUCTION BY DAVID HANNAY

London

MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited

NEW YORK: THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

1897

All rights reserved

INTRODUCTION

Among the few subjects which are still left at the disposal of theduly-gifted writer of romance is the Pirate. Not but that many havewritten of pirates. Defoe, after preparing the ground by a pamphletstory on the historic Captain Avery, wrote The Life, Adventures, andPiracies of Captain Singleton. Sir Walter Scott made use in somewhatthe same fashion of the equally historic Gow—that is to say, his piratebears about the same relation to the marauder who was suppressed byJames Laing, that Captain Singleton does to Captain Avery. Michael Scotthad much to say of pirates, and he had heard much of them during hislife in the West Indies, for they were then making their last fightagainst law and order. The pirate could not escape the eye of Mr. R. L.Stevenson, and accordingly we have an episode of pirates in the episodeof the Master of Ballantrae. Balsac, too, wrote Argow le Pirateamong the stories which belong to the years when he was exhausting allthe ways in which a novel ought not to be written. Also the pirate is acommonplace in boys' books. Yet for as much as he figures in stories forold and young, it may be modestly maintained that nobody has ever yetdone him quite right.

Defoe's Captain Singleton is a harmless, thrifty, and ever moral pirate,of whom it is impossible to disapprove. Sir Walter's is a mildgentleman, concerning whom one wonders how he ever came to be in suchcompany. Michael Scott's pirate is a bloodthirsty ruffian enough, andyet it is difficult to feel that a person who dressed in such a highlypicturesque manner, and who was commonly either a Don or a Scotchgentleman of ancient descent, was quite the real thing. Mr. Stevenson'spirate is nearer what one knows must have been the life. He is acowardly, lurking, petty scoundrel. John Silver is certainly somethingvery different, but then when Mr. Stevenson drew the commanding figurein Treasure Island he was not making a portrait of a pirate, but wasonly making play with the well-established puppet of boys' books. Yet,after all, the pirate, if he was not such an agreeable rascal as JohnSilver, was not always the greedy, spiritless rogue drawn in the Masterof Ballantrae. To do him properly and as he was, he ought to beapproached with a mixture of humour and morality, and also with aknowledge of the facts concerning him, which to the best of my knowledgehave never been combined in any writer.

Captain Johnson, in his valuable General History of the Pirates fromtheir First Rise and Settlement in the Island of Providence to thepresent time, begins with antiquity. He mounts up the dark backwardabyss of time till he meets with the pirates who captured Julius Caesar,and were suppressed by Pompey. This is not necessary. Our pirate was avery different fellow from those broken men of th