THE IMMORTALS

By DAVID DUNCAN

Illustrated by Dick Francis

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Galaxy Magazine October 1960.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Staghorn dared tug at the veil that hid the

future. Maybe it wasn't a crime to look ...

maybe it was just that the future was ugly!

I

Dr. Clarence Peccary was an objective man. His increasing irritationwas caused, he realized, by the fear that his conscience was going tointervene between him and the vast fortune that was definitely withinhis grasp. Millions. Billions! But he wanted to enjoy it.

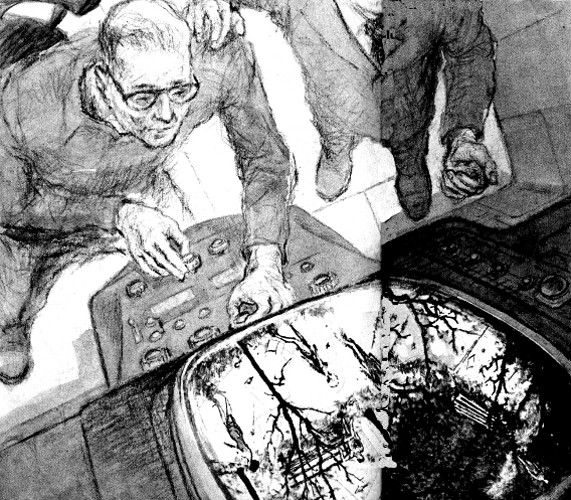

He didn't want to skulk through life avoiding the eyes of everyone hemet—particularly when his life might last for centuries. So he satglowering at the rectangular screen that was located just above thecontrol console of Roger Staghorn's great digital computer.

At the moment Peccary was ready to accuse Staghorn of having noconscience whatsoever. It was only through an act of scientificdetachment that he reminded himself that Staghorn neither had a fortuneto gain nor cared about gaining one. Staghorn's fulfillment was inHumanac, the name he'd given the electronic monster that presentlyclaimed his full attention. He sat at the controls, his eyes luminousbehind the magnification of his thick lenses, his lanky frame archedforward for a better view of Humanac's screen. Far from showingannoyance at what he saw, there was a positive leer on his face.

As well there might be.

On the screen was the full color picture of a small park in whatappeared to be the center of a medium-sized town. It was a shabbylittle park. Rags and tattered papers waggled indolently in the breeze.The grass was an unkempt, indifferent pattern of greens and browns, asthough the caretaker took small pains in setting his sprinklers. Beyondthe square was a church, its steeple listing dangerously, its windowsbroken and its heavy double doors sagging on their hinges.

Staghorn's leers and Dr. Peccary's glowers were not for the scenery,however, but for the people who wandered aimlessly through the littlepark and along the street beyond, carefully avoiding the area beneaththe leaning steeple. All of them were uniformly young, ranging fromperhaps seventeen at one extreme to no more than thirty at the other.When Dr. Peccary had first seen them, he'd cried out joyfully, "Yousee, Staghorn, all young! All handsome!" Then he'd stopped talking ashe studied those in the foreground more closely.

Their clothing, to call it that, was most peculiar. It was rags.

Here and there was a garment that bore a resemblance to a dress orjacket or pair of trousers, but for the most part the people simply hadchunks of cloth wrapped about them in a most careless fashion. Severalwould have been arrested for indecent exposure had they appearedanywhere except on Humanac's screen. However, they seemed indifferentto this—and to all else. A singularly attractive girl, in a costumethat would have made a Cretan blush, didn't even get a second glancefrom, a young Adonis who passed her on the walk. Nor did she bestow oneon him. The park bench held more interest for her, so she sat down onit.

Peccary studied her more closely, then straightened with