Transcribed from the 1912 A. C. Fifield edition by DavidPrice,

The Note-Books of

Samuel Butler

Author of “Erewhon”

Selectionsarranged and edited by

Henry Festing Jones

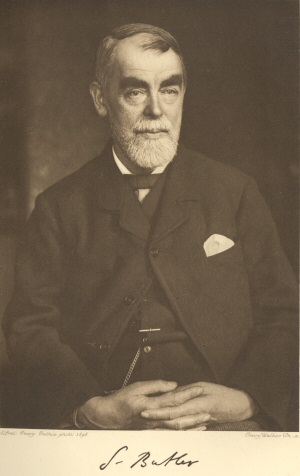

Withphotogravure portrait by Emery Walker from a

photograph taken by Alfred Cathie in1898

London

A. C. Fifield, 13 Clifford’s Inn, E.C.

1912

WILLIAMBRENDON AND SON, LTD., PRINTERS, PLYMOUTH

Preface

Early in his life Samuel Butlerbegan to carry a note-book and to write down in it anything hewanted to remember; it might be something he heard some one say,more commonly it was something he said himself. In one ofthese notes he gives a reason for making them:

“One’s thoughts fly so fast that one must shootthem; it is no use trying to put salt on their tails.”

So he bagged as many as he could hit and preserved them,re-written on loose sheets of paper which constituted a sort ofmuseum stored with the wise, beautiful, and strange creaturesthat were continually winging their way across the field of hisvision. As he became a more expert marksman his collectionincreased and his museum grew so crowded that he wanted acatalogue. In 1874 he started an index, and this led to hisreconsidering the notes, destroying those that he rememberedhaving used in his published books and re-writing theremainder. The re-writing shortened some but it lengthenedothers and suggested so many new ones that the index was soon oflittle use and there seemed to be no finality about it(“Making Notes,” pp. 100–1 post). In 1891he attached the problem afresh and made it a rule to spend anhour every morning re-editing his notes and keeping his index upto date. At his death, in 1902, he left five bound volumes,with the contents dated and indexed, about 225 pages of closelywritten sermon paper to each volume, and more than enough unboundand unindexed sheets to made a sixth volume of equal size.

In accordance with his own advice to a young writer (p. 363post), he wrote the notes in copying ink and kept a pressed copywith me as a precaution against fire; but during his lifetime,unless he wanted to refer to something while he was in mychambers, I never looked at them. After his death I tookthem down and went through them. I knew in a general waywhat I should find, but I was not prepared for such a multitudeand variety of thoughts, reflections, conversations,incidents. There are entries about his early life atLangar, Handel, school days at Shrewsbury, Cambridge,Christianity, literature, New Zealand, sheep-farming, philosophy,painting, money, evolution, morality, Italy, speculation,photography, music, natural history, archæology, botany,religion, book-keeping, psychology, metaphysics, theIliad, the Odyssey, Sicily, architecture, ethics,the Sonnets of Shakespeare. I thought of publishingthe books just as they stand, but too many of the entries are ofno general interest and too many are of a kind that must wait ifthey are ever to be published. In addition to theseobjections the confusion is very great. One would look inthe e