Star-Crossed Lover

By WILLIAM W. STUART

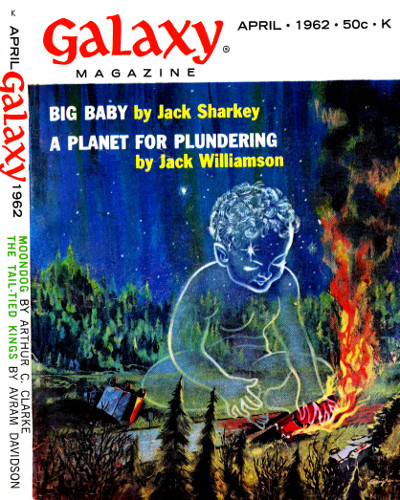

Illustrated by RITTER

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Galaxy Magazine April 1962.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

She was a wonderful wife—sweet, pretty,

loving—but she would keep littering up

the house with her old, used-up bodies!

I

So help me, I'm not really a fiend, a monstrous murderer or aBluebeard. I am not, truly, even a mad scientist bucking for a billingto top Frankenstein's. My knowledge of science ends with the Sundaymagazine section of the paper. As for the bodies of all those women thefront pages claim I butchered and buried somewhat carelessly out by thegarage, all that is just—well, just an illusion of sorts.

Equally illusory, I am hoping, is my reservation for a sure seat, nextperformance, in the electric chair which now seems so certain after themerest formality of a trial.

Actually I am, or was, nothing but a very normal, average—upper middleaverage, that is—sort of a guy. I have always been friendly, sociable,kindly, lovable to a fault. So how did lovable, kindly old I happen toget into such a bloody mess?

I simply helped a little old lady cross the street. That's all.

All right, I admit I was old for Boy Scout work. But the poor old batdid look mighty confused and baffled, standing there on the corner ofYork and Grand Avenue, looking vaguely around.

So, "What the hell," I said to myself; and, to her, "Can I help you,Madam?" I had to cross the street anyway. Traffic being what it was, Ifigured I'd feel a little safer with her for company. It was silly, ofcourse, to think that a poor old lady on my arm would ever inhibit theGrand Avenue throughway traffic but I tried it. Good job I did, too.

It was an early fall afternoon, a bit before rush hour. I had knockedoff work early. It was too nice a day for work and besides the managingeditor had fired me again. I had nothing better to do, so I thought I'dwander over to Maxim's for a drink or two. Then, on the corner, I foundthe old lady.

She was a pretty sad-looking old lady. Matter of fact she was—juststanding there, not even trying—the worst-looking old lady I eversaw. She looked, to put it kindly, like a three-day corpse that hadmade it the hard way after a century of poor health. First I thought,hell, I'll give the old bag of misery a boost, shove her under a bus orsomething. It would be the decent, kindly thing to do.

I spoke, tentatively. She half-turned and looked up at me from herwitch's crouch. The eyes in the beak-nosed, ravaged ruin of a face werebig, luminous, a glowing green. They clearly belonged elsewhere andthere was a lost, appealing look in them. There was a demand there,too.

"I—uh—that is, would you care to cross with me, Madam?" I asked her.

She took my arm. There was a moment's lull in the wake of a screamingprowl car. I muttered a word of prayer and we were off the curb. Theold hag was surprisingly quick. It looked as though we were going tomake it. Then, three-quarters across, I came down with a rubber heel inan oil slick just as a roaring, grinding cement-mixer truck was comingdown on me like an avalanche. My feet went up. I gave the old witch ashove clear and shut my eyes for fear the coming sight of smeared bloodand guts—my own—would make me sick.

And then, instead of a prone, cringing heap on the pavement sweatingout the ten-to-one odds agains