THE IRISH PENNY JOURNAL.

| Number 29. | SATURDAY, JANUARY 16, 1841. | Volume I. |

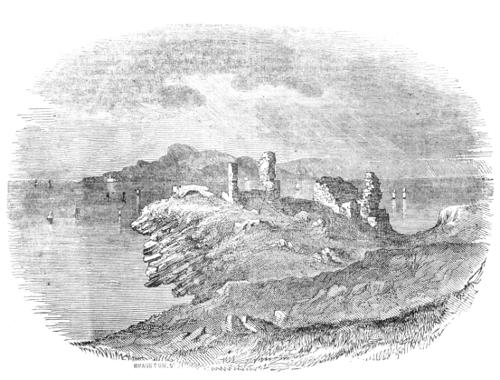

KILBARRON CASTLE, COUNTY OF DONEGAL.

We think our readers generally will concur with us in consideringthe subject of our prefixed illustration as a verystriking and characteristic one—presenting features which,except among the castles of the Scottish highland chiefs, willonly be found on the wild shores of our own romantic island.It is indeed a truly Irish scene—poetical and picturesque in theextreme, and its history is equally peculiar, being wholly unlikeany thing that could be found relating to any castle outof Ireland.

From the singularity of its situation, seated on a lofty,precipitous, and nearly insulated cliff, exposed to the stormsand billows of the western ocean, our readers will naturallyconclude that this now sadly dilapidated and time-worn ruinmust have owed its origin to some rude and daring chief ofold, whose occupation was war and rapine, and whose thoughtswere as wild and turbulent as the waves that washed his sea-girteagle dwelling; and such, in their ignorance of its unpublishedhistory, has been the conclusion drawn by moderntopographers, who tell us that it is supposed to have been thehabitation of freebooters. But it was not so; and our readerswill be surprised when we acquaint them that this lonely,isolated fortress was erected as an abode for peaceful men—asafe and quiet retreat in troubled times for the laborious investigatorsand preservers of the history, poetry, and antiquitiesof their country! Yes, reader, this castle was theresidence of the ollaves, bards, and antiquaries of the peopleof Tirconnell—the illustrious family of the O’Clerys, towhose zealous labours in the preservation of the history andantiquities of Ireland we are chiefly indebted for the informationon those subjects with which we so often endeavour toinstruct and amuse you. You will pardon us, then, if with agrateful feeling to those benefactors of our country to whoselabours we owe so much, we endeavour to do honour to theirmemory by devoting a few pages of our little national workto their history, as an humble but not unfitting monument totheir fame.

We trust, however, that such a sketch as we proposewill not be wholly wanting either in interest or instruction.It will throw additional light upon the ancientcustoms and state of society in Ireland, and exhibit in astriking way a remarkable feature in the character of our countrymenof past ages, which no adverse circumstances were everable utterly to destroy, and which, we trust, will again distinguishthem as of old—their love for literature and learning,and their respect for good and learned men. It willalso exhibit another trait in their national character no lesspeculiar or remarkable, namely, their great anxiety to preservetheir family histories—a result of which is, that even tothe present day the humblest Irish peasant, as well as theestated gentleman, can not unfrequently trace his descent notonly to a more remote period, but also with a greater abundanceof historical evidence than most of the princely familiesof Europe. This is, indeed, a trait in the national characterwhich philosophers, and men like ourselves, usually affect[Pg 226]to hold in contempt. But no species of knowledge should bedespised; and the desire to penetrate the dim obscurities oftime in search of ou