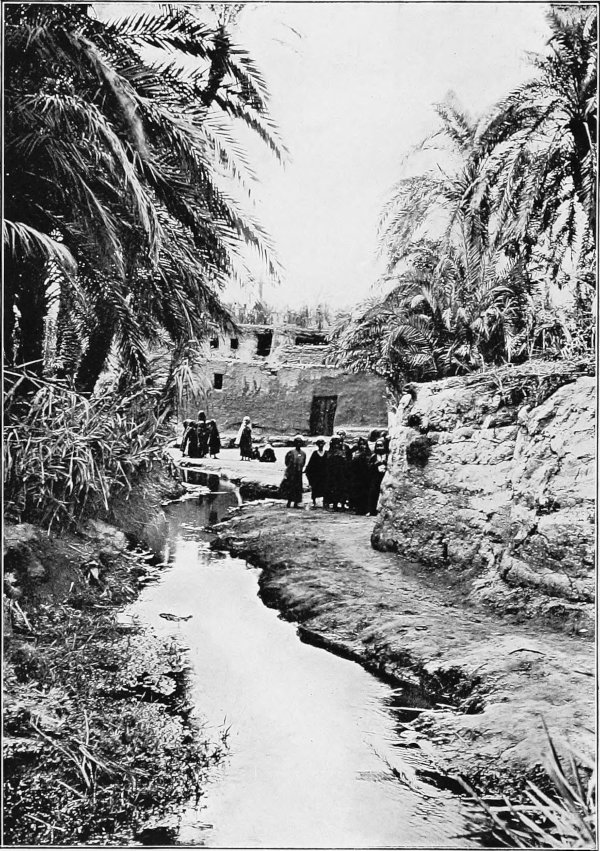

AIN ESTAKHERAB, GENNAH

AN EGYPTIAN OASIS

ANACCOUNT OF THE OASIS OF KHARGA

IN THE LIBYAN DESERT, WITHSPECIAL

REFERENCE TO ITS HISTORY,PHYSICAL

GEOGRAPHY, AND WATER-SUPPLY

BY H. J.LLEWELLYN BEADNELL

F.G.S., F.R.G.S., Assoc.Inst.M.M.

FORMERLY OF THE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OFEGYPT

WITH MAPS ANDILLUSTRATIONS

LONDON

JOHN MURRAY,ALBEMARLE STREET, W.

1909

TO THE

MEMORY OF A FRIEND AND FELLOW-GEOLOGIST,

THOMAS BARRON,

WHO LOST HIS LIFE IN THE SUDAN

IN FEBRUARY, 1906

[vii]

PREFACE

The inhabited depressionsof the Libyan Desert, called by Herodotus the ‘Islands of theBlest,’ are interesting alike to the archæologist, to thegeographer and geologist, and to the tourist who wishes to wanderfrom the well-beaten tracks, and perhaps none more so than theOasis of Kharga, lying 130 miles west of Luxor—the site of ancientThebes—and recently connected by railway with the Nile Valley.

Descended from the ancient Libyans, the inhabitants of theEgyptian oases (numbering over 30,000 souls) are quite distinctfrom the Fellahin and Bedawin of the Nile Valley. Isolated by aridand desolate wastes, these communities occupy quaint walled-intowns and villages, tucked away among groves of palms, interspersedwith smiling gardens and fields of corn. Rain is almost unknown,and rivers are non-existent, the trees and crops being irrigated bybubbling wells, deriving their waters from deep-seated sources.

Kharga—the subject of the present memoir—[viii]formed part of the Great Oasis ofancient days, and was governed in turn by the Pharaohs, the PersianMonarchs, and the Roman Emperors. Through it the ill-fated army ofCambyses is recorded to have marched, and in it is to be seen themost important Persian monument in Egypt, the temple of Hibis. Butmost interesting of all is the wonderfully preserved EarlyChristian necropolis, dating from the time of Bishop Nestorius, whowas banished to Kharga in A.D. 434.Juvenal, Athanasius, and other celebrities likewise appear to havemade unwilling acquaintance with this portion of the RomanEmpire.

The character of the people at the present day—a curious mixtureof stupidity, apathy, and shrewdness—seems to reflect in greatmeasure their past history, as well as the peculiar conditionsunder which they still live. A history of the inhabitants since thewithdrawal of the Roman garrisons would resolve itself into anaccount of an endless combat with Nature, which, with sand and windas its chief agents, has never abated its efforts to recover thosetracts which the Ancients, by the exercise of much skill andindustry, wrested from the desert.