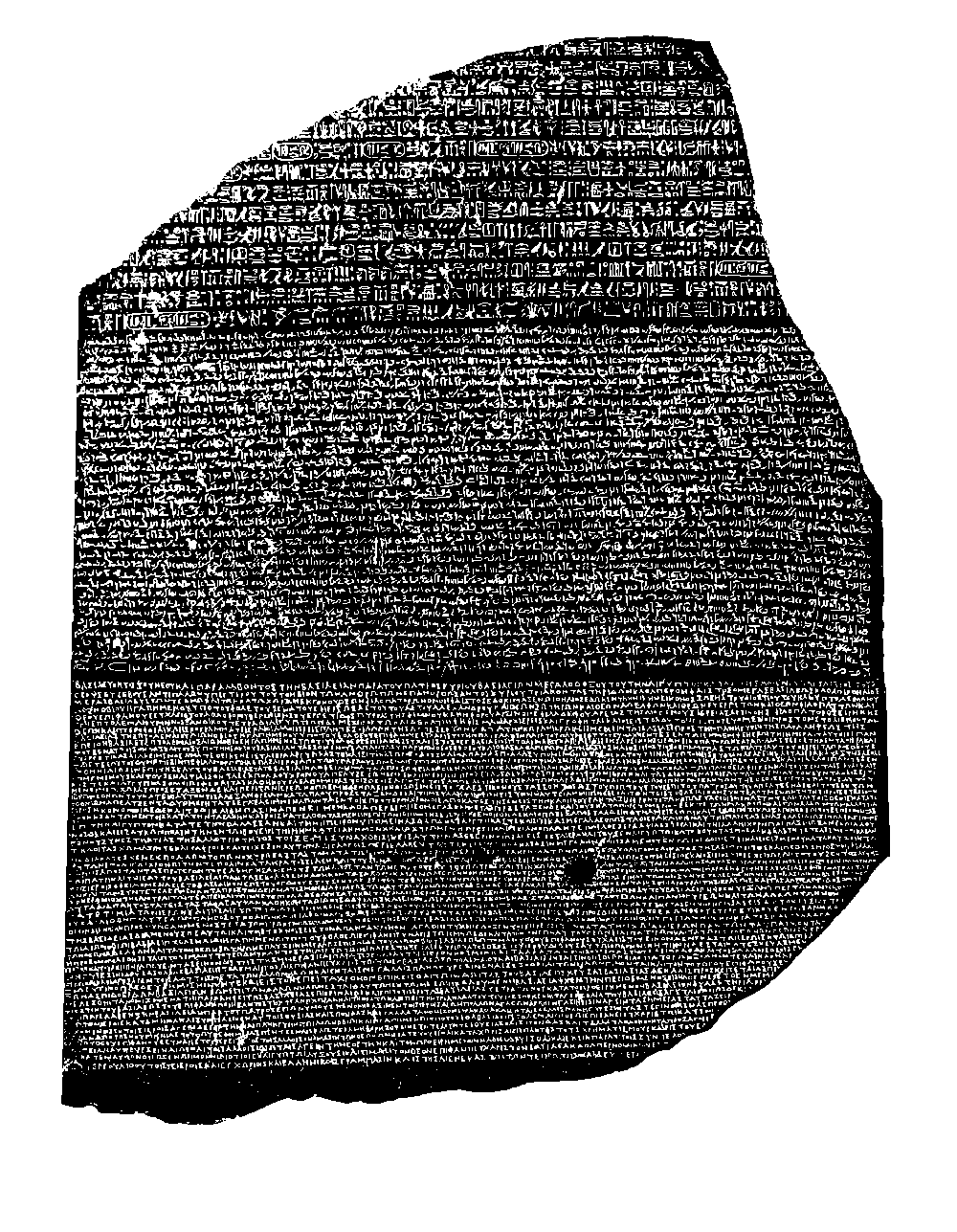

THE ROSETTA STONE.

THE DISCOVERY OF THE STONE.

The famous slab of black basalt which stands at the southern end of theEgyptian Gallery in the British Museum, and which has for more than acentury been universally known as the “Rosetta Stone,” was found at aspot near the mouth of the great arm of the Nile that flows throughthe Western Delta to the sea, not far from the town of “Rashîd,” or as Europeanscall it, “Rosetta.” According to one account it was found lying on the ground,and according to another it was built into a very old wall, which a company ofFrench soldiers had been ordered to remove in order to make way for the foundationsof an addition to the fort, afterwards known as “Fort St. Julien.”[1] The actualfinder of the Stone was a French Officer of Engineers, whose name is sometimesspelt Boussard, and sometimes Bouchard, who subsequently rose to the rank ofGeneral, and was alive in 1814. He made his great discovery in August, 1799.Finding that there were on one side of the Stone lines of strange characters,which it was thought might be writing, as well as long lines of Greek letters,Boussard reported his discovery to General Menou, who ordered him to bringthe Stone to his house in Alexandria. This was immediately done, and the Stonewas, for about two years, regarded as the General’s private property. WhenNapoleon heard of the Stone, he ordered it to be taken to Cairo and placed in the“Institut National,” which he had recently founded in that city. On its arrivalin Cairo it became at once an object of the deepest interest to the body of learnedmen whom Napoleon had taken with him on his expedition to Egypt, and theEmperor himself exhibited the greatest curiosity in respect of the contents of theinscriptions cut upon it. He at once ordered a number of copies of the Stone tobe made for distribution among the scholars of Europe, and two skilled lithographers,“citizens Marcel and Galland,” were specially brought to Cairo fromParis to make them. The plan which they followed was to cover the surface of theStone with printer’s ink, and then to lay upon it a sheet of paper which they rolledwith india-rubber rollers until a good impression had been taken. Several of theseink impressions were sent to scholars of great repute in many parts of Europe, andin the autumn of 1801 General Dagua took two to Paris, where he committed themto the care of “citizen Du Theil” of the Institut National of Paris.

1. This fort is marked on Napoleon’s Map of Egypt, and it stood on the left or west bank of the Rosettaarm of the Nile.

THE ARRIVAL OF THE STONE IN ENGLAND.

After the successful operations