LIFE AND ADVENTURES

OF

PETER WILKINS

VOL. I.

BY ROBERT PALTOCK,

Of Clement's Inn.

WITH A PREFACE BY A. H. BULLEN,

Editor Of "The Works Of John Day,"

"A Collection Of Old English Plays," Etc.

PREFACE.

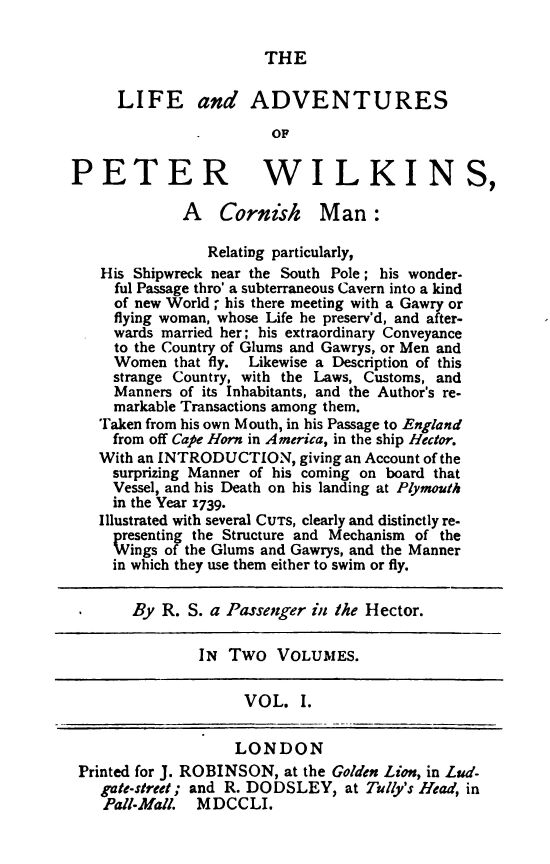

In one of those bright racy essays at which modern dulness delights to sneer, Hazlitt discussed the question whether the desire of posthumous fame is a legitimate aspiration; and the conclusion at which he arrived was that there is "something of egotism and even of pedantry in this sentiment." It is a true saying in literature as in morality that "he that seeketh his life shall lose it." The world cares most for those who have cared least for the world's applause. A nameless minstrel of the North Country sings a ballad that shall stir men's hearts from age to age with haunting melody; Southey, toiling at his epics, is excluded from Parnassus. Some there are who have knocked at the door of the Temple of Fame, and have been admitted at once and for ever. When Thucydides announced that he intended his history to be a "possession for all time," there was no mistaking the tone of authority. But to be enthroned in state, to receive the homage of the admiring multitude, and then to be rejected as a pretender,—that is indeed a sorry fate, and one that may well make us pause before envying literary despots their titles. The more closely a writer shrouds himself from view, the more eager are his readers to get a sight of him. The loss of an arm or a leg would be a slight price for a genuine student to pay if only he could discover one new fact about Shakespeare's history. I will not attempt to impose on the reader's credulity by professing myself eager to acquire information about the author of "Peter Wilkins" at such a sacrifice; but it would have been a sincere pleasure to me if I could have brought to light some particulars about one whose personality must have possessed a more than ordinary charm. The delightful voyage imaginaire here presented to the reader was first published in 1751.*

* Some copies are said to be dated 1750. It appears on the list of new books announced in the "Gentleman's Magazine" for November 1750.

An edition appeared immediately afterwards at Dublin; so the book must have had some sale. The introduction and the dedication to the Countess of Northumberland (to whom it will be remembered Percy dedicated his "Reliques" and Goldsmith the first printed copy of his "Edwin and Angelina") are signed with the