$1,000 A Plate

By JACK McKENTY

Illustrated by BECK

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

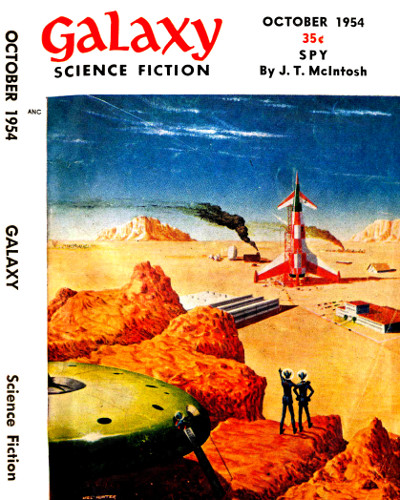

Galaxy Science Fiction October 1954.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

When Marsy Gras shot off its skyrockets, Mars

Observatory gave it the works—fireworks!

Sunset on Mars is a pale, washed out, watery sort of procedure that ishardly worth looking at. The shadows of the cactus lengthen, the sungoes down without the slightest hint of color or display and everythingis dark. About once a year there is one cloud that turns pink briefly.But even the travel books devote more space describing the new signadorning the Canal Casino than they do on the sunset.

The night sky is something else again. Each new crop of tourists goesto bed at sunrise the day after arrival with stiff necks from lookingup all night. The craters of the moons are visible to the naked eye,and even a cheap pair of opera glasses can pick out the buildings ofthe Deimos Space Station.

A typical comment from a sightseer is, "Just think, Fred, we were wayup there only twelve hours ago."

At fairly frequent intervals, the moons eclipse. The local Chamber ofCommerce joins with the gambling casinos to use these occasions asexcuses for a celebration. The "Marsy Gras" includes floats, costumes,liquor, women, gambling—and finishes off with a display of fireworksand a stiff note of protest from the nearby Mars Observatory.

The day after a particularly noisy, glaring fireworks display, the topbrass at the Observatory called an emergency meeting. The topic wasnot a new one, but fresh evidence, in the form of several still-wetphotographic plates, showing out-of-focus skyrocket trails and a galaxyof first-magnitude aerial cracker explosions was presented.

"I maintain they fire them in our direction on purpose," one scientistdeclared.

This was considered to be correct because the other directions aroundtown were oil refineries and the homes of the casino owners.

"Why don't we just move the Observatory way out in the desert?" atechnician demanded. "It wouldn't be much of a job."

"It would be a tremendous job," said Dr. Morton, the physicist. "Ifnot for the glare of city lights on Earth, we wouldn't have had to moveour telescopes to the Moon. If not for the gravel falling out of thesky on the Moon, making it necessary to resurface the reflectors everyweek, we wouldn't have had to move to Mars. Viewing conditions here arejust about perfect—except for the immense cost of transporting theequipment, building materials, workmen, and paying us triple time forworking so far from home. Why, did you ever figure the cost of a singlephotographic plate? What with salaries, freight to and from Earth,maintenance and all the rest, it's enormous!"

"Then why don't we cut down the cost of ruined exposures," asked thetechnician, "by moving the Observatory away from town?"

"Because," Dr. Morton explained, "we'd have to bring in crews to tearthe place down, other crews to move it, still more crews to rebuild it.Not to mention unavoidable breakage and replacement, which involve morefreight from Earth. At $7.97 per pound dead-weight ... well, you figureit out."

"So we can't move and we can't afford ruined thousand-dollar plates,"said the scientist who had considered himself a target for thefireworks. "Then what's the answer?"