Transcriber’s Note

The punctuation and spelling from the original text have been faithfully preserved. Only obvioustypographical errors have been corrected.

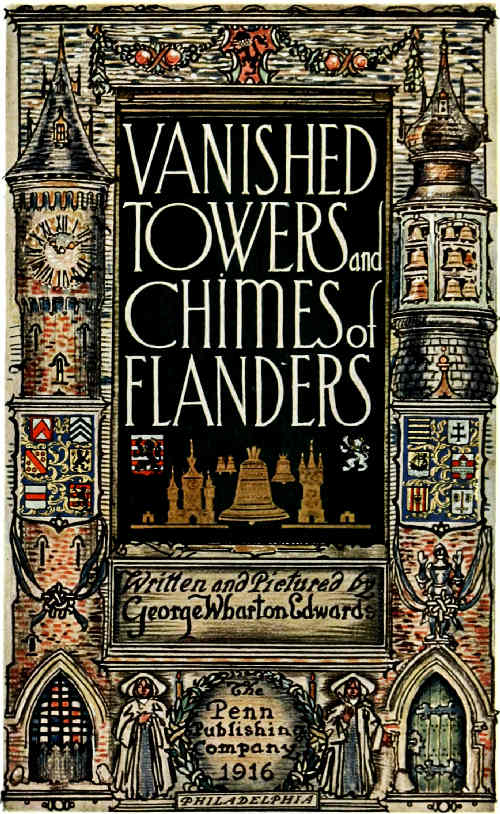

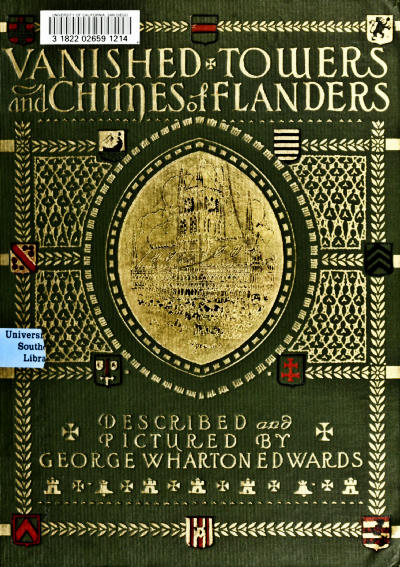

COPYRIGHT

1916 BY

GEORGE

WHARTON

EDWARDS

Vanished Towers and Chimes of Flanders

FOREWORD

The unhappy Flemish people, who are at present much in the lime-light,because of the invasion and destruction of their once smiling and happylittle country, were of a character but little known or understood bythe great outside world. The very names of their cities and townssounded strangely in foreign ears.

Towns named Ypres, Courtrai, Alost, Furnes, Tournai, were in thebeginning of the invasion unpronounceable by most people, but little bylittle they have become familiar through newspaper reports of thebarbarities said to have been practised upon the people by the invaders.Books giving the characteristics of these heroic people are eagerlysought. Unhappily these are few, and it would seem that these veryinadequate and random notes of mine upon some phases of the lives ofthese people, particularly those related to architecture, and the musicof their renowned chimes of bells, might be useful.

That the Fleming was not of an artistic nature I found during myresidence in these towns of Flanders. The great towers and wondrousarchitectural marvels throughout this smiling green flat landscapeappealed to him not at all. He was not interested in either art, music,or literature. He was of an intense practical nature. I am of coursespeaking of the ordinary or "Bourgeois" class now. Then, too, the classof great landed proprietors was numerically very small indeed, the landgenerally being parcelled or hired out in small squares or holdings bythe peasants themselves. Occasionally the commune owned the land, andsublet portions to the farmers at prices controlled to some extent bythe demand. Rarely was a "taking" (so-called) more than five acres or soin extent. Many of the old "Noblesse" are without landed estates, andthis, I am informed, was because their lands were forfeited when theFrench Republic annexed Belgium, and were never restored to them. Thusthe whole region of the Flemish littoral was given over to smallholdings which were worked on shares by the peasants under generalconditions which would be considered intolerable by the Anglo-Saxon. Acommon and rather depressing sight on the Belgian roads at dawn of day,were the long lines of trudging peasants, men, women and boys hurryingto the fields for the long weary hours of toil lasting often into thedark of night. But we were told they were working for their own profit,were their own masters, and did not grumble. This grinding toil in the