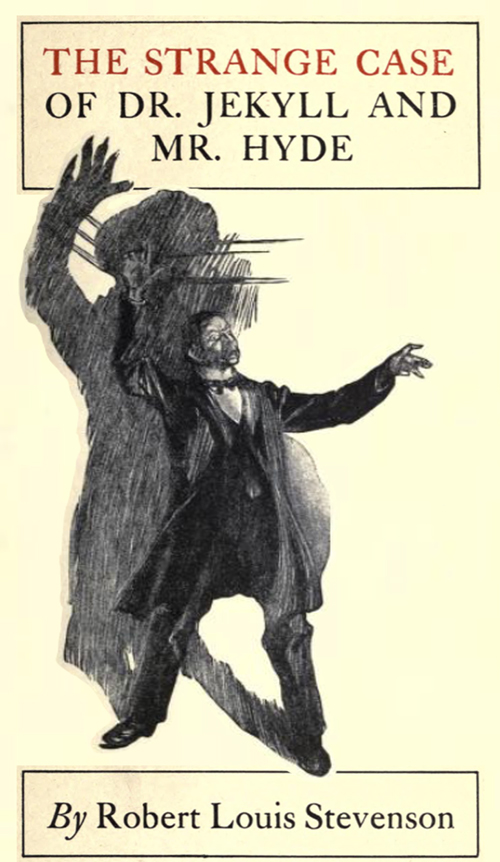

The Strange Case Of Dr. Jekyll And Mr. Hyde

by Robert Louis Stevenson

Contents

STORY OF THE DOOR

Mr. Utterson the lawyer was a man of a rugged countenance that was neverlighted by a smile; cold, scanty and embarrassed in discourse; backward insentiment; lean, long, dusty, dreary and yet somehow lovable. At friendlymeetings, and when the wine was to his taste, something eminently humanbeaconed from his eye; something indeed which never found its way into histalk, but which spoke not only in these silent symbols of the after-dinnerface, but more often and loudly in the acts of his life. He was austere withhimself; drank gin when he was alone, to mortify a taste for vintages; andthough he enjoyed the theatre, had not crossed the doors of one for twentyyears. But he had an approved tolerance for others; sometimes wondering, almostwith envy, at the high pressure of spirits involved in their misdeeds; and inany extremity inclined to help rather than to reprove. “I incline toCain’s heresy,” he used to say quaintly: “I let my brother goto the devil in his own way.” In this character, it was frequently hisfortune to be the last reputable acquaintance and the last good influence inthe lives of downgoing men. And to such as these, so long as they came abouthis chambers, he never marked a shade of change in his demeanour.

No doubt the feat was easy to Mr. Utterson; for he was undemonstrative at thebest, and even his friendship seemed to be founded in a similar catholicity ofgood-nature. It is the mark of a modest man to accept his friendly circleready-made from the hands of opportunity; and that was the lawyer’s way.His friends were those of his own blood or those whom he had known the longest;his affections, like ivy, were the growth of time, they implied no aptness inthe object. Hence, no doubt the bond that united him to Mr. Richard Enfield,his distant kinsman, the well-known man about town. It was a nut to crack formany, what these two could see in each other, or what subject they could findin common. It was reported by those who encountered them in their Sunday walks,that they said nothing, looked singularly dull and would hail with obviousrelief the appearance of a friend. For all that, the two men put the greateststore by these excursions, counted them the chief jewel of each week, and notonly set aside occasions of pleasure, but even resisted the calls of business,that they might enjoy them uninterrupted.

It chanced on one of these rambles that their way led them down a by-street ina busy quarter of London. The street was sm