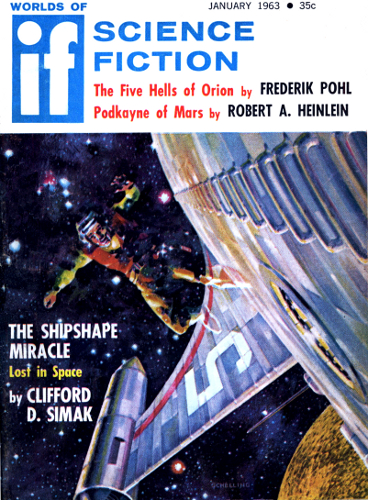

THE SHIPSHAPE MIRACLE

BY CLIFFORD D. SIMAK

The castaway was a wanted man—but he

didn't know how badly he was wanted!

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Worlds of If Science Fiction, January 1963.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

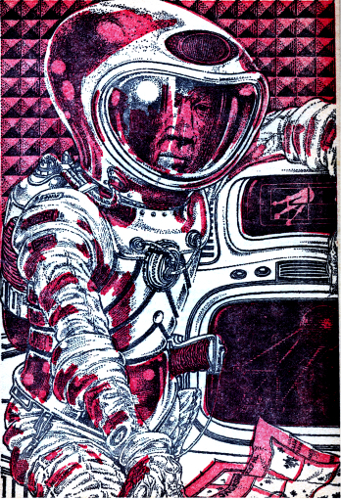

If Cheviot Sherwood ever had believed in miracles, he believed in themno longer. He had no illusions now. He knew exactly what he faced.

His life would come to an end on this uninhabited backwoods planet andthere'd be none to mourn him, none to know. Not, he thought, that therewould be any mourners, under any circumstance. Although there werethose who would be glad to see him, who would come running if they knewwhere he might be found.

These were people, very definitely, that Sherwood had no desire to see.

His great, one might say his overwhelming, desire not to see themcould account in part for his present situation, since he had taken offfrom the last planet of record without filing flight plans and lackingclearance.

Since no one knew where he might have headed and since his radio wasjunk, there was no likelihood at all that anyone would find him—evenif they looked, which would be a matter of some doubt. Probably themost that anyone would do would be to send out messages to otherplanets to place authorities on the alert for him.

And since his spaceship, for the lack of a certain valve for which hehad no replacement, was not going anywhere, he was stuck here on thisplanet.

If that had been all there had been to it, it might not have been sobad. But there was a final irony that under other circumstances (ifit had been happening to someone else, let's say), would have keptSherwood in stitches of forthright merriment for hours on end at thevery thought of it. But since he was the one involved, there was nomerriment.

For now, when he could gain no benefit, he was potentially rich beyondeven his own most greedy and most lurid dreams.

On the ridge above the camp he'd get up beside his crippled spaceshiplay a strip of clay-cemented conglomerate that fairly reeked withdiamonds. They lay scattered on the hillside, washed out by theweather; they were mixed liberally in the gravel of the tiny streamthat wended through the valley. They could be picked up by the basket.They were of high quality; there were several, the size of humanskulls, that probably were priceless.

Sherwood was of a hardy, rough and tumble breed. Once he becameconvinced of his situation he made the best of it. He made his campinto a home and laid in supplies—digging roots, gathering nuts,drying fish and making pemmican. If he was to be cast in the role of aRobinson Crusoe, he proposed to be at least comfortably well fed.

In his spare time he gathered diamonds, dumping them in a pile outsidehis shack. And in the idle afternoons or the long evenings, he satbeside his campfire and sorted them out—washing them free of clingingdirt and grading them according to their size and brilliance. The verybest of them he put into a sack, designed for easy grabbing if thetime should ever come when he might depart the planet.

Not that he had any hope this would come about.

Even so, he was a man who planned against contingencies. He alwaystried to have some sort of loop-ho