E-text prepared by Louise Pryor, Jacqueline Jeremy,

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

()

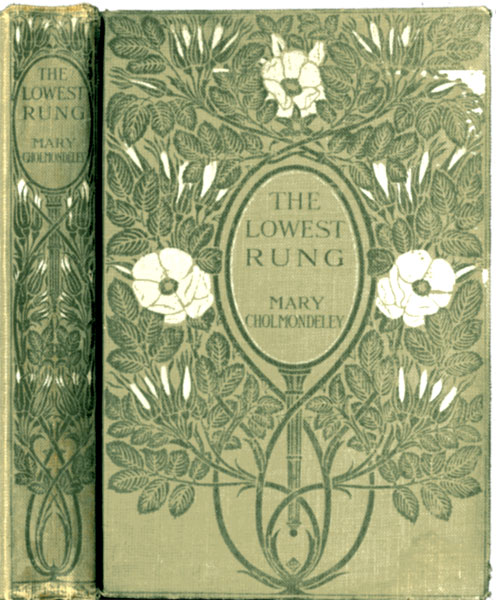

THE LOWEST RUNG

THE LOWEST RUNG

TOGETHER WITH THE HAND ON

THE LATCH, ST. LUKE'S SUMMER

AND THE UNDERSTUDY

BY MARY CHOLMONDELEY

author of "red pottage"

LONDON

JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET, W.

1908

COPYRIGHT, 1908, IN THE

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

TO

HOWARD STURGIS

CONTENTS

[9]PREFACE

I have been writing books for five-and-twenty years, novels of which Ibelieve myself to be the author, in spite of the fact that I have beenassured over and over again that they are not my own work. When I haveon several occasions ventured to claim them, I have seldom beenbelieved, which seems the more odd as, when others have claimed them,they have been believed at once. Before I put my name to them they wereinvariably considered to be, and reviewed as, the work of a man; and foryears after I had put my name to them various men have been mentioned tome as the real author.

I remember once, when I was very young and shy, how at one of my firstLondon dinner-parties a charming elderly man discussed one of my[10]earliest books with such appreciation that I at last remarked that I hadwritten it myself. If I had looked for a surprised flash of delight atthe fact that so much talent was palpitating in white muslin beside him,I was doomed to be disappointed. He gravely and gently said, "I knowthat to be untrue," and the conversation was turned to other subjects.

One man did indeed actually announce himself to be the author of "RedPottage," in the presence of a large number of people, including thelate Mr. William Sharp, who related the occurrence to me. But theincident ended uncomfortably for the claimant, which one would havethought he might have foreseen.

But whether my books are mine or not, still whenever one of them appearsthe same thing happens. I am pressed to own that such-and-such acharacter "is taken from So-and-so." I have not yet yielded to theseexhortations to confession, partly, no doubt, because it would be very[11]awkward for me afterwards if I owned that thirty different persons werethe one and only original of "So-and-so."

My character for uprightness (if I ever had one) has never survived mytacit, or in some cases emphatic, refusal to be squeezed thro