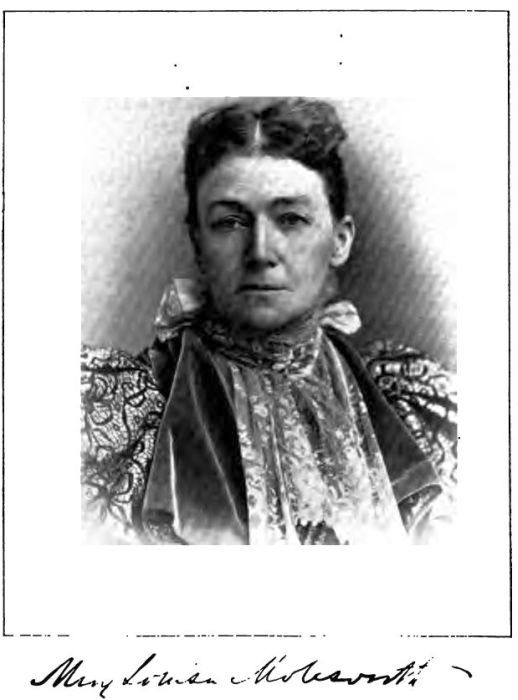

Mrs Molesworth

"The Laurel Walk"

Chapter One.

A Rainy Evening.

There was a chemist’s shop at Craig Bay, quite a smart chemist’s shop, with plate-glass windows and the orthodox “purple” and other coloured jars of Rosamund fame. It was one of the inconsistencies of the place, of which there were several. For Craig Bay was far from being a town; it was not even a big village, and the two or three shops of its early days were of the simplest and quaintest description, emporiums of a little of everything, into which you made your way by descending two or three steps below the level of the rough pavement outside. The chemist’s shop was the first established, I think, of the new order of things, when the place and neighbourhood suddenly rose into repute as peculiarly bracing and healthy from the mingling of sea and hill air with which they were favoured. It was kept in countenance now by several others, a draper’s, a stationer’s, a photographer’s, of course, besides the imperative butcher’s, fishmonger’s, and so on, some of which subsided into closed shutters and vacancy after the “season” was over and the visitors had departed. For endeavours which had been made to introduce a winter season had not been crowned with success. The place was too out-of-the-way, the boasted mildness of climate not altogether to be depended upon. But the chemist’s shop stood faithfully open all the year round, doing a little business in wares not, strictly speaking, belonging to it, such as note-paper and even books, when the library-and-stationer’s in one had gone to sleep for the time.

On a cold raw evening in late November, Betty Morion stood waiting for her sister Frances on the door-step of the shop. It would have been warmer inside, but Betty had her fancies, like many other people, and one of them was a dislike to the smell of drugs, with which “inside,” naturally, was impregnated. And she was thickly clad and fairly well used to cold and to damp—even to rain—for to-night it was drizzling depressingly.

“I wish Francie would be quick,” thought the girl more than once during the first few moments of her waiting, though she knew it was certainly not poor Frances’ fault. Their father’s prescriptions had always some very special and peculiar directions accompanying them, and Betty knew of old that the waiting for them was apt to be a long affair.

And she was not of an impatient nature. After a while she forgot about the tiresomeness, and fell to watching the reflections of the brilliant colours of the jars in the puddles and on the surface of the wet pavement just below her, as she had often watched them before. They were pretty—in a sense—and yet somehow they made the surrounding dreariness drearier.

“I wonder if it does rain more here than anywhere else,” she said to herself dreamily. “What a splashing walk home we shall have! I wish we did not live up a hill—at least I think I wish we didn’t, though perhaps if our house was down here I should wish it was higher up! Perhaps it doesn’t really rain more at Craig Bay than at other places, but we notice it more. For nearly everything pleasant that ever comes to us depends on the weather.” And Betty sighed. “I could fancy,” she went on, “living in a way that would make one scarcely care what it was like out of doors. A beautiful big house with ferneries and conservatories, and lovely rooms to wander about in, and a library full of delightful books, and lots of people to stay with us and—well, yes, of course, it would be