POLLONY UNDIVERTED

By SYDNEY VAN SCYOC

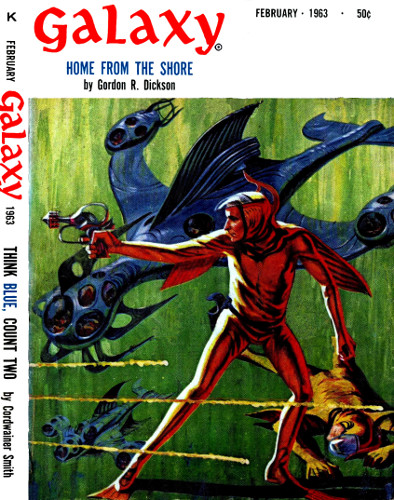

Illustrated by R. D. Francis

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Galaxy Science Fiction February 1963.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

With the whole world at her doorstep, what

she wanted was completely out of reach!

Pollony's dream formed around a glare of light, a tang of men's lotion.Then she was awake to Brendel poking her.

"I'm hungry."

She struggled to burrow back into sleep.

"I'm starving, kid. I can't sleep."

She bleared at the timespot. It was three a.m. "Go 'way."

"Aw, gimme an omelette." Brendel ate a lot lately. His features werecoarsening from it; his body was plumpening.

She argued and protested and whined, and he hit her. But it didn't makeher feel good any more when he hit her.

Kitchen Central was inop for the night. She punched Storage. Driedingredients materialized on the cookgrid, a flat metal sheet set intothe countertop.

Later, as she took the omelette up, she heard Brendel setting the operatapes. She scowled. But when opera shattered their live she dropped theskillet and cried, "Oh! Do we have to listen to that trash?" Her voicewas more weary than shrill. The opera routine was getting old.

"What you calling trash?" He twitched his plump shoulders.

"It makes me sick!"

He spat profanity.

It wasn't a good fight. He knew something was wrong and he hit her toohard. She slugged back, hurt her hand, cursed, ran and locked herselfinto the sleep.

She was asleep when he came pounding. She woke and pointed the lockopen. She glared.

He said nothing. He ordered his smaller collections—his miniaturehorses, his ballpoint pens and his old-time cereal box missiles—onto his storeshelf before mounting his sleepshelf and pointing out thelight.

She could hear him not sleeping.

Finally he muttered, "Too damn much cheese but it was okay."

She said nothing. She didn't almost cry as she might have a monthbefore.

Brendel had appeared on their grid a year before, a dark, pugnaciousyoung man, jittering and nervous. "Clare Webster around?"

"Mother isn't here." Her mother collected men. She met them at drinkingclubs or collector meets. She gave them her grid card and took theirs,making them promise to come see her. If a man came, she tacked his cardon her bulletin board. If he came twice or three times, she marked hiscard with colored pencil.

Brendel twitched his shoulders. "I got the evening. Wanta have dinner,kid?"

She was seventeen and tired of collecting china roosters and peach-canlabels. She was tired of seeing the same stupid people every day.Somewhere there was someone handsome and perfect, and she had to findhim and become perfect too. She couldn't waste all her life beingstupid like her mother.

It took her two hours to see that Brendel was the perfect person. Hewas handsome, aggressive, easy to be with. He quarreled all the timeand he even had a full-time job.

She married him. She dropped her little-girl collections anddiversions. She was no longer a formless adolescent. She was verysolid, very adult.

But the solidness had gone. She had found that Brendel's aggressivenessmasked fear; his quarrelsomeness masked insecurity. Worst, he had noimagination. He plodded.

It had begun two weeks before. Brendel had come home from work tightand tense. He tried eating, he tried