Ye of Little Faith

By Rog Phillips

Illustrated by TOM BEECHAM

[Transcriber Note: This etext was produced from IF Worlds of ScienceFiction January 1953. Extensive research did not uncover any evidencethat the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

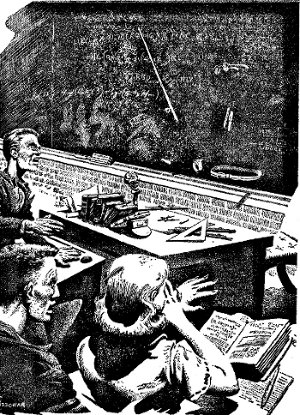

The disappearance of John Henderson was most spectacular. It occurredwhile he was at the blackboard working an example in multipleintegration for his ten o'clock class. The incompleted problem remainedon the board for three days while the police worked on the case. It, awrist watch and a sterling silver monogrammed belt buckle, lying on thefloor near where he had stood, were all the physical evidence they hadto go on.

There was plenty of eye-witness evidence. The class consisted offorty-three pupils. They all had their eyes on him in varying degrees ofattention when it happened. Their accounts of what happened all agreedin important details. Even as to what he had been saying.

In the reports that went into the police files he was quoted with a highdegree of certainty as having said, "Integration always brings into thepicture a constant which was not present. This constant of integrationis, in a sense, a variable. But a different type of variable than themathematical unknown. It might be said to be a logical variable—"

The students were in unanimous agreement and, at this point, Dr.Henderson came to an abrupt stop in his lecture. Suddenly, an expressionof surprise appeared on his face. It was succeeded by an exclamation oftriumph. And he simply vanished from the spot.

He didn't fade away, rise, drop into the floor, or take any timevanishing. He simply stopped being there.

He just wasn't there any more.

The police searched his room in the nearby Vanderbilt Arms Hotel. Theyturned a portrait of the missing math professor to the newspapers topublish. Arbright University offered a reward of one hundred dollars toanyone who had seen him.

The police also found a savings pass book in his room. It had a balanceof three thousand eight hundred and forty dollars, which had been builtup to that figure by steady monthly deposits over a period of years. Italso had a withdrawal of three hundred and twenty dollars two daysbefore the disappearance. They were sure they were on the path to amotive. This avenue of exploration came to an abrupt end with thediscovery that he had traded in his last year's car on a new one, andthat sum had been necessary to complete the deal.

After the third day the blackboard had been erased and the classroomreleased for its regular classes. Police enthusiasm dropped to the normof what they called legwork. Finding out who the missing man'sacquaintances and friends were, calling on them and talking to them inthe hopes of picking up something they could go on.

They passed Martin Grant by because they had heard from him in theirinitial work. In fact, he had been a little too present for theirtastes.

After ten days they dropped the case from the active blotter. TheUniversity, seeing that there was little likelihood of having to shellout the reward money, increased it to five hundred dollars.

But Martin Grant continued to ponder over a conversation he himself hadhad with