Security Plan

By JOSEPH FARRELL

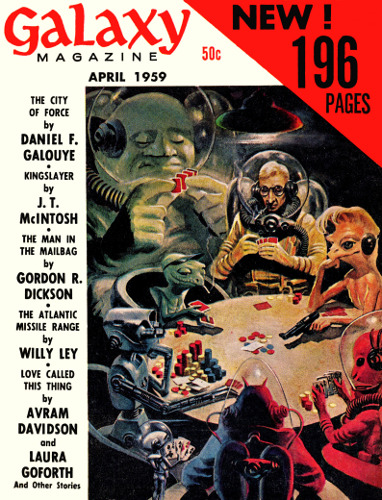

Illustrated by WOOD

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Galaxy Magazine April 1959.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

I had something better than investing for

the future ... the future investing in me!

"My mother warned me," Marilyn said again, "to think twice before Imarried a child prodigy. Look for somebody good and solid, she said,like Dad—somebody who will put something away for your old age."

I tapped a transistor, put a screwdriver across a pair of wires andwatched the spark. Marilyn was just talking to pass the time. Shereally loves me and doesn't mind too much that I spend my spare timeand money building a time machine. Sometimes she even believes that itmight work.

She kept talking. "I've been thinking—we're past thirty now andwhat do we have? A lease on a restaurant where nobody eats, and atime machine that doesn't work." She sighed. "And a drawerful ofpawn tickets we'll never be able to redeem. My silver, my camera, mytypewriter...."

I added a growl to her sigh. "My microscope, my other equipment...."

"Uncle Johnson will have them for his old age," she said sadly. "Andwe'll be lucky if we have anything."

I felt a pang of resentment. Uncle Johnson! It seemed that every time Iacquired something, Uncle Johnson soon came into possession of it. We'dbeen kids together, although he was quite a few years older, a hulkinglout in the sixth grade while I was in the first, and I graduated fromgrammar school a term ahead of him. Of course I went on to high schooland had a college degree at fifteen, being a prodigy. Johnson went towork in his uncle's pawn shop, sweeping the floor and so on, and that'swhen we started calling him Uncle.

This wasn't much of a job because Johnson's uncle got him to work foralmost nothing by promising he would leave him the pawn shop when hedied. And it didn't look as if much would come of this, because theuncle was not very old and he was always telling people a man couldn'tafford to die these days, what with the prices undertakers werecharging.

Before I had even started to shave, I had a dozen papers published inscientific journals, all having to do with the nature of time. Timetravel became my ambition and I was sure I saw a way to build a timemachine. But it took years to work out the details, and nobody seemedinterested in my work, so I had to do it all myself. Somehow I stoppedworking long enough to get a wife, and we had to eat. So we ran thislittle hash house and lived in the back room, and at least we got ourfood wholesale.

And Johnson's uncle fell down the cellar stairs and split his skullopen. So Johnson became the owner of a thriving business after givinghis uncle a simple funeral, because he knew his uncle wouldn't havewanted him to waste any more money on that than he had to.

"But we have a time machine," Marilyn said fondly. "That's somethingJohnson would give us a lot on—if it worked."

"We almost have a time machine," I said, looking around at my life'swork. Our kitchen was the time machine, with a great winding of wiresaround it to create the field I had devised. The doors had been aproblem that I solved by making them into switches, so that when theywere closed the coils made the complete circuit of the room.

"Almost," I repeated. "After twenty years of work, I am through exceptfor a few small items—"