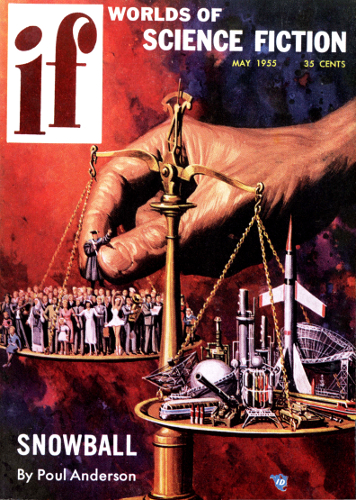

SNOWBALL

BY POUL ANDERSON

Simon's new source of power

promised a new era for Mankind. But

what happens to world economy when

anyone can manufacture it in the

kitchen oven?... Here's one answer!

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Worlds of If Science Fiction, May 1955.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

It did not come out of some government laboratory employing a thousandbright young technicians whose lives had been checked back to the crib;it was the work of one man and one woman. This is not the reversal ofhistory you might think, for the truth is that all the really basicadvances have been made by one or a few men, from the first to stealfire out of a volcano to E=mc2. Later, the bright young techniciansget hold of it, and we have transoceanic airplanes and nuclear bombs;but the idea is always born in loneliness.

Simon Arch was thirty-two years old. He came from upstateMassachusetts, the son of a small-town doctor, and his childhood andadolescence were normal enough aside from tinkering with mathematicsand explosive mixtures. In spite of shyness and an overly largevocabulary, he was popular, especially since he was a good basketballplayer. After high school, he spent a couple of tedious years in thetail-end of World War II clerking for the Army, somehow never gettingoverseas; weak eyes may have had something to do with that. In hisspare time he read a great deal, and after the war he entered M.I.T.with a major in physics. Everybody and his dog was studying physicsthen, but Arch was better than average, and went on through a series ofgraduate assistantships to a Ph.D. He married one of his students andpatented an electronic valve. Its value was limited to certain specialapplications, but the royalties provided a small independent income andhe realized his ambition: to work for himself.

He and Elizabeth built a house in Westfield, which lies some fiftymiles north of Boston and has a small college—otherwise it is only ashopping center for the local farmers. The house had a walled gardenand a separate laboratory building. Equipment for the lab was expensiveenough to make the Arches postpone children; indeed, after itsrequirements were met, they had little enough to live on, but they madesarcastic remarks about the installment-buying rat race and kept out ofit. Besides, they had hopes for their latest project: there might bereal money in that.

Colin Culquhoun, professor of physics at Westfield, was Arch's closestfriend—a huge, red-haired, boisterous man with radical opinions onpolitics which were always good for an argument. Arch, tall and slimand dark, with horn-rimmed glasses over black eyes and a boyishlysmooth face, labelled himself a reactionary.

"Dielectrics, eh?" rumbled Culquhoun one sunny May afternoon. "Sothat's your latest kick, laddie. What about it?"

"I have some ideas on the theory of dielectric polarization," saidArch. "It's still not too well understood, you know."

"Yeh?" Culquhoun turned as Elizabeth brought in a tray of dewedglasses. "Thank'ee kindly." One hairy hand engulfed a goblet and hedrank noisily. "Ahhhh! Your taste in beer is as good as your taste inpolitics is moldy. Go on."

Arch looked at the floor. "Maybe I shouldn't," he said, feeling hisold nervousness rise within him. "You see, I'm operating purely on ahunch. I've got the math pretty well whipped into shape, but it allrests on an unproven postulat