Transcriber’s Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

THE LIFE AND REIGN OF EDWARD I.

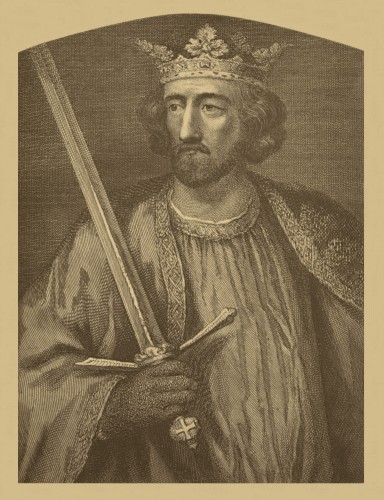

EDWARD I.

After the Engraving by Vertue, from the Statue atCarnarvon Castle.

THE LIFE AND REIGN

OF EDWARD I.

BY THE AUTHOR OF

“THE GREATEST OF THE PLANTAGENETS.”

Pactum Serva.

SEELEY, JACKSON, & HALLIDAY, FLEET STREET,

LONDON. MDCCCLXXII.

London:

Printed by Simmons & Botten,

Shoe Lane, E.C.

PREFACE.

The volume entitled “The Greatest of the Plantagenets,”was correctly described in its title‐page, as “an HistoricalSketch.” Nothing more than this was contemplated bythe writer. The compilation was made among the manuscriptsof the British Museum, in the leisure mornings ofone spring and summer; and so soon as a fair copy hadbeen taken, it was handed to the printer. The work wasregarded as little else than a contribution towards anaccurate review of what is both the most interesting andthe most neglected period of our English history.

Its reception exceeded by far the author’s anticipations.Very naturally—it might be said, quite inevitably—manyof those who admitted the general truth of the narrative,were ready to charge the writer with “partisanship,” andwith taking a “one‐sided vie” of the question. It isnot easy to see how this could have been avoided. Agreat literary authority has said, that the first requisite fora good biography is, that the writer should be possessedwith an honest enthusiasm for his subject. And in thepresent case his chief object was to protest against whatvihe deemed to be injustice. It was his sincere belief, that forabout a century past an erroneous estimate of this greatking’s character had been commonly presented to the Englishpeople. He endeavoured to show that this had beenthe case; to explain the causes, and to lead men’s mindsto what he deemed to be the truth. Such a task couldhardly be performed without giving large opportunity toan objector to exclaim, “You write in a partisan spirit.”

When a new view of any passage in history is presented,many fair and honourable men, while they yieldto the force of evidence, cannot help feeling some reluctance—somedislike to the sudden change of beliefwhich is asked of them. Such men will often be foundto object to the manner in which their old opinion hasbeen assailed, even while they admit that that opinionwas erroneous, and can no longer be maintained.

So, in this case, even those who advanced this chargeof partisanship were generally ready to concede, that analtered view of Edward’s character had been not onlypropounded, but in a great measure established. Thusthe Dean of Chichester, Dr. Hook, while he “differswidely from some of the author’s conclusions,” admitsthat “his argument is always worthy of attention,” anddescribes the volume as one in which “everything thatcan be advanced in favour of Edward is powerfullystated.”1 So, too