Being one of the richest men in the world,it was only natural that many people anticipatedthe day he would die. For someone should claim—

Mr. Chipfellow's Jackpot

by

Dick Purcell

"I'm getting old," Sam Chipfellowsaid, "and old mendie."

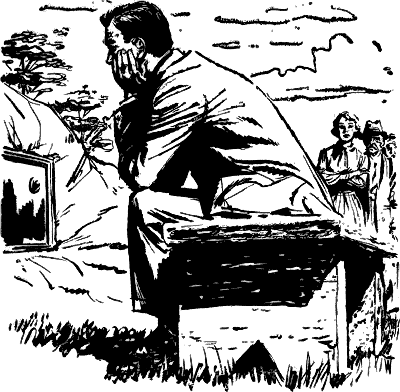

His words were an indirect answerto a question from Carter Hagen,his attorney. The two menwere standing in an open glade,some distance from Sam Chipfellow'smansion at Chipfellow's Folly,this being the name Sam himselfhad attached to his huge estate.

Sam lived there quite alone exceptfor visits from relatives andthose who claimed to be relatives.He needed no servants nor help ofany kind because the mansion wascompletely automatic. Sam did notlive alone from choice, but he washighly perceptive and it made himuncomfortable to have relatives aroundwith but one thought in theirminds: When are you going to dieand leave me some money?

Of course, the relatives couldhardly be blamed for entertainingthis thought. It came as naturally asbreathing because Sam Chipfellowwas one of those rare individuals—ascientist who had made money; allkinds of money; more money thanalmost anybody. And after all, hisrelatives were no different thanthose of any other rich man. Theyfelt they had rights.

Sam was known as The Geniusof the Space Age, an apt title becausethere might not have been anyspace without him. He had beenextremely versatile during his longcareer, having been responsible forthe so-called eternal metals—metalagainst which no temperature, corrosive,or combinations of corrosiveswould prevail. He was also thepioneer of telepower, the science ofcontrol over things mechanicalthrough the electronic emanationsof thought waves. Because of hisinvestigations into this power, menwere able to direct great ships bymerely "thinking" them on theirproper courses.

These were only two of his contributionsto progress, there beingmany others. And now, Sam wasfacing the mystery neither he norany other scientist had ever beenable to solve.

Mortality.

There was a great deal of activitynear the point at which the menstood. Drills and rock cutters hadformed three sides of an enclosurein a ridge of solid rock, and now agiant crane was lowering thick slabsof metal to form the walls. Nearby,waiting to be placed, lay the slabwhich would obviously become thedoor to whatever Sam was building.Its surface was entirely smooth,but it bore great hinges and somesort of a locking device was builtin along one edge.

Carter Hagen watched the activityand considered Sam's reply tohis question. "Then this is to be amausoleum?"

Sam chuckled. "Only in a sense.Not a place to house my dead bonesif that's what you mean."

Carter Hagen, understanding thislonely old man as he did, knew furtherquestions would be useless. Samwas like that. If he wanted you toknow something, he told you.

So Carter held his peace and theyreturned to the mansion where Samgave him a drink after they concludedthe business he had come on.

Sam also gave Carter somethingelse—an envelope. "Put that in yoursafe, Carter. You're comparativelyyoung. I'm taking it for grantedyou will survive me."

"And this is—?"

"My will. All old men shouldleave wills and I'm no exception tothe rule. When I'm dead, open itand read what's inside."

Carter Hagen regarded the envelopewith speculation. Samsmiled. "If you're wonde