Transcribed from the 1912 Chapman & Hall edition ,

GEORGE BORROW

THE MAN AND HIS BOOKS

by

EDWARD THOMAS

Author of

“THE LIFE OF RICHARD JEFFERIES,”“LIGHT AND TWILIGHT,” “REST AND UNREST,” “MAURICEMAETERLINCK,” Etc.

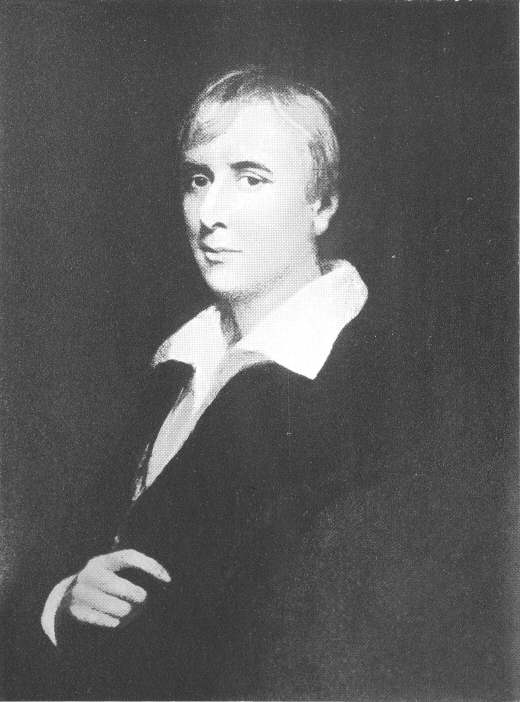

WITH PORTRAITS AND ILLUSTRATIONS

LONDON

CHAPMAN & HALL, Ltd.

1912

Printed by

Jas. Truscott and Son, Ltd.,

London, E.C.

NOTE

The late Dr. W. I. Knapp’s Life (John Murray) and Mr. Watts-Dunton’sprefaces are the fountains of information about Borrow, and I have clearlyindicated how much I owe to them. What I owe to my friend, Mr.Thomas Seccombe, cannot be so clearly indicated, but his prefaces havebeen meat and drink to me. I have also used Mr. R. A. J. Walling’ssympathetic and interesting “George Borrow.” The Britishand Foreign Bible Society has given me permission to quote from Borrow’sletters to the Society, edited in 1911 by the Rev. T. H. Darlow; andMessrs. T. C. Cantrill and J. Pringle have put at my disposal theirpublication of Borrow’s journal of his second Welsh tour, wonderfullyannotated by themselves (“Y Cymmrodor,” 1910). Theseand other sources are mentioned where they are used and in the bibliography.

DEDICATION TO E. S. P. HAYNES

My Dear Haynes,

By dedicating this book to you, I believe it is my privilege to introduceyou and Borrow. This were sufficient reason for the dedication. The many better reasons are beyond my eloquence, much though I haveremembered them this winter, listening to the storms of CaermarthenBay, the screams of pigs, and the street tunes of “Fall in andfollow me,” “Yip-i-addy,” and “The first goodjoy that Mary had.”

Yours,

EDWARD THOMAS.

Laugharne,

Caermarthenshire,

December, 1911.

p. 1CHAPTERI—BORROW’S AUTOBIOGRAPHY

The subject of this book was a man who was continually writing abouthimself, whether openly or in disguise. He was by nature inclinedto thinking about himself and when he came to write he naturally wroteabout himself; and his inclination was fortified by the obvious impressionmade upon other men by himself and by his writings. He has beendead thirty years; much has been written about him by those who knewhim or knew those that did: yet the impression still made by him, andit is one of the most powerful, is due mainly to his own books. Nor has anything lately come to light to provide another writer on Borrowwith an excuse. The impertinence of the task can be tempered onlyby its apparent hopelessness and by that necessity which Voltaire didnot see.

I shall attempt only a re-arrangement of the myriad details accessibleto all in the writings of Borrow and about Borrow. Such re-arrangementwill sometimes heighten the old effects and sometimes modify them. The total impression will, I hope, not be a smaller one, though it mustinevitably be softer, less clear, less isolated, less gigantic. I do not wish, and I shall no