THE RAG AND BONE MEN

By ALGIS BUDRYS

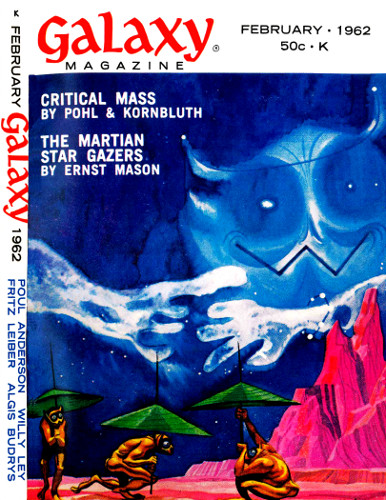

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Galaxy Magazine February 1962.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Unfortunate castaway! Marooned

far from home—with nothing to

share his loneliness but humans!

The other one—Charpantier, he called himself—he and I were going backup the hill to the Foundation, carrying our bags, when I happened toremark I didn't think the Veld was sane anymore. (I call myself Maurer.)

Charpantier said nothing for a moment. We kept walking, up the gravelpath between the unimaginatively clipped hedges. But he was frowning alittle, and after a while he said in an absent way: "Now, how would onedetermine that?" He looked straight into my eyes, which is somethingthat has always upset me, and challenged: "I don't think one could."

I felt the shock of inadequacy. Words come out of me—perfectlyaccurate words, I know; but I never know how, and sometimes when askedI forget.

Now I must be very lucid; I must be his kind of man, I thought, andpicked my way among my words. "These things he's had us get," I said,putting the burlap bag down and stopping so as to hold Charpantier inone place.

"He wants to build something unEarthly," Charpantier said, annoyedbecause I was playing his kind of trick on him, and so baldly. "Whatstandards do you propose to judge by?"

But I was right and he was wrong. Now it remained to make him see how."Yes. He wants to build something unEarthly. Out of Earthly parts.He wants to take six radio tubes for an Earthly radio, three piecesof Earthly Lucite exactly 1/4 Earthly inch thick, a roll of Earthly16-gauge wire, a General Electric heat lamp, and all these otherthings—the polystyrene foam blocks, the polyurethane plastic sheeting,the polyvinyl insulating tape; what have you in your bag, Charpantier?Out of all this, he wants to make a Veldish thing."

"He's spent years learning about Earthly things," Charpantier pointedout. "For years, we've brought him books. Men. Everything he needs.Now he's learned what the Earthly equivalents of Veldish materialsare, and he's ready to make his new transporter." Charpantier had adark face—dark hair, dark beard, dark eyes. When his dark brows drewtogether it was easy to see that his best expression was dark scorn.

"I think he's desperate," I said. "I think he's learned all he can.He's learned what the nearest Earthly equivalents to Veldish thingsare. And he's learned that all Earth can give him nothing closer. Idon't see how he could do better. Even he. You cannot make apples ofcabbages. But he wants to get home—you know he wants so much to leavehere and get home—and now he's desperate, and is going to try makinga new transporter out of materials nothing like those in the one thatbroke and marooned him here."

"And it won't function?" Charpantier asked. "There is that risk. Butwhy shouldn't he try? What's insane in that?"

"I fear it might work. I fear it might work in ways a transportershould not." And I shivered, for if I say something I feel it, and I donot feel anything I don't believe is right. I have been wrong, but notoften ... or perhaps I forget.

Charpantier smiled. "How should a Veld transporter work?"

"That's not the point!" I cried at Charpantier's obstinacy in beingCharpantier. "I don't have to know. The Veld has to know, and be insaneenough to try something different. Look—" I said, searching,