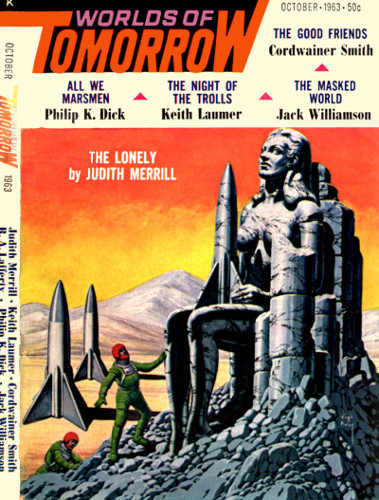

THE NIGHT OF THE TROLLS

BY KEITH LAUMER

ILLUSTRATED BY NODEL

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Worlds of Tomorrow October 1963

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

The machine's job was to defend its place against

enemies—but it had forgotten it had friends!

I

It was different this time. There was a dry pain in my lungs, and adeep ache in my bones, and a fire in my stomach that made me want tocurl into a ball and mew like a kitten. My mouth tasted as though micehad nested in it, and when I took a deep breath wooden knives twistedin my chest.

I made a mental note to tell Mackenzie a few things about his petcontrolled-environment tank—just as soon as I got out of it. Isquinted at the over-face panel: air pressure, temperature, humidity,O-level, blood sugar, pulse and respiration—all okay. That wassomething. I flipped the intercom key and said, "Okay, Mackenzie, let'shave the story. You've got problems...."

I had to stop to cough. The exertion made my temples pound.

"How long have you birds run this damned exercise?" I called. "I feellousy. What's going on around here?"

No answer.

This was supposed to be the terminal test series. They couldn't all beout having coffee. The equipment had more bugs than a two-dollar hotelroom. I slapped the emergency release lever. Mackenzie wouldn't likeit, but to hell with it! From the way I felt, I'd been in the tankfor a good long stretch this time—maybe a week or two. And I'd toldGinny it would be a three-dayer at the most. Mackenzie was a greattechnician, but he had no more human emotions than a used-car salesman.This time I'd tell him.

Relays were clicking, equipment was reacting, the tank cover slidingback. I sat up and swung my legs aside, shivering suddenly.

It was cold in the test chamber. I looked around at the dull graywalls, the data recording cabinets, the wooden desk where Mac sat bythe hour re-running test profiles—

That was funny. The tape reels were empty and the red equipment lightwas off. I stood, feeling dizzy. Where was Mac? Where were Bonner andDay, and Mallon?

"Hey!" I called. I didn't even get a good echo.

Someone must have pushed the button to start my recovery cycle;where were they hiding now? I took a step, tripped over the cablestrailing behind me. I unstrapped and pulled the harness off. The effortleft me breathing hard. I opened one of the wall lockers; Banner'spressure suit hung limply from the rack beside a rag-festooned coathanger. I looked in three more lockers. My clothes were missing—evenmy bathrobe. I also missed the usual bowl of hot soup, the happy facesof the techs, even Mac's sour puss. It was cold and silent and emptyhere—more like a morgue than a top priority research center.

I didn't like it. What the hell was going on?

There was a weather suit in the last locker. I put it on, set thetemperature control, palmed the door open and stepped out into thecorridor. There were no lights, except for the dim glow of theemergency route indicators. There was a faint, foul odor in the air.

I heard a dry scuttling, saw a flick of movement. A rat the size ofa red squirrel sat up on his haunches and looked at me as if I weresomething to eat. I made a kicking motion and he ran off, but not veryfar.

My heart was starting to thump a little harder now. The way it doeswhen you begin to realize that something's wrong—bad wron