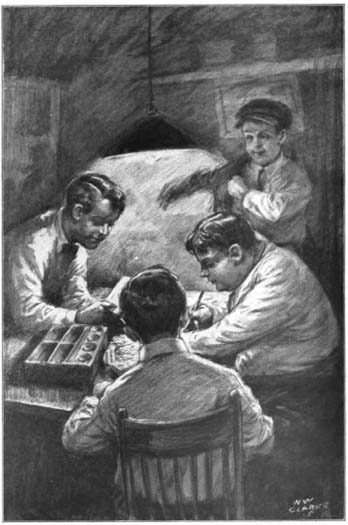

WE SHUT UP THE DOORS AND COUNTED UP TO SEE WHAT WE’D DONE

MARK TIDD IN BUSINESS

CHAPTER I

The Wicksville paper told how therewouldn’t be any school for six weeks, onaccount of somebody getting diphtheria. Thatsame afternoon my father didn’t get out of theway of an automobile and got broke insidesome place, so he had to go to the hospitalin Detroit to have it fixed.

“James,” says my mother—that’s my realname, but the fellows call me Plunk—“I’ve—I’vegot to go with—your father.” Shewas crying, you see, and I wasn’t feeling verygood, I can tell you. “And,” she went on,“I don’t know what—we shall ever do.”

“About what?” I asked her, having noidea myself.

“The store,” she says.

I saw right off. You see, my father is Mr.Smalley, and he owns Smalley’s Bazar, whereyou can buy almost anything—if father canfind where he put it. With father gone andmother gone there wouldn’t be anybody leftto look after the store, and so there wouldn’tbe any money, because the store was wheremoney came from, and then as sure as shootingthe Smalley family would have a hardtime of it. It made me gloomier than ever,especially because I didn’t seem to be ableto think of any way to help.

Mother went up-stairs to father’s room,shaking her head and crying, and I went outdoorsbecause there didn’t seem to be anythingelse to do. I opened the door andstepped out on the porch, and right thatminute I began to feel easier in my mind,somehow. The thing that did it was justseeing who was sitting there, almost fillingup a whole step from side to side. It was aboy, and he was so fat his coat was ’mostbusted in the back where he bulged, and hisname was Mark Tidd. That’s short forMarcus Aurelius Fortunatus Tidd, and youmaybe have heard of him on account of thestories Tallow Martin and Binney Jenks havetold about him. Yes, sir, the sight of himmade me feel a heap better.

“Hello, P-plunk!” he stuttered. “How’syour f-f-father?”

“Got to go to the hospital,” says I, “andmother’s goin’, too, and there won’t be anybodyto mind the store, and there won’t beany money, and we don’t know what we’rea-goin’ to do.” I was ’most cryin’, but Ididn’t let on any more than I could help.

“W-what’s that?” asks Mark.

I told him all over again, and he squintedup his little eyes and began pinching his fatcheek like he does when he’s studying hardover something.

“L-looks bad, don’t it?” he says.

“Awful,” says I.

“M-must