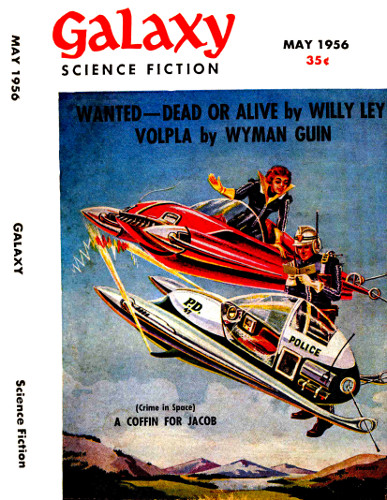

Volpla

By WYMAN GUIN

Illustrated by DICK FRANCIS

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Galaxy Science Fiction May 1956.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

The only kind of gag worth pulling, I always

maintained, was a cosmic one—till I learned the

Cosmos has a really nasty sense of humor!

There were three of them. Dozens of limp little mutants that would havesent an academic zoologist into hysterics lay there in the metabolicaccelerator. But there were three of them. My heart took a greatbound.

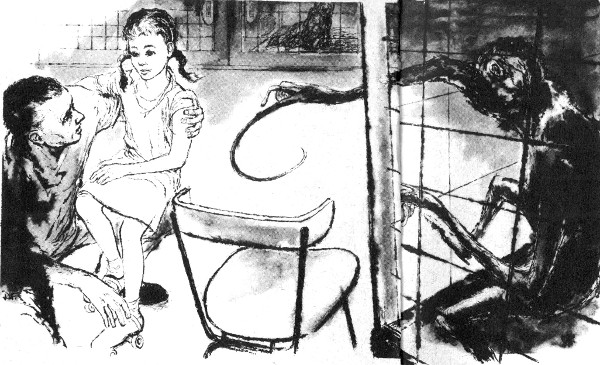

I heard my daughter's running feet in the animal rooms and herrollerskates banging at her side. I closed the accelerator and walkedacross to the laboratory door. She twisted the knob violently, tryingto hit a combination that would work.

I unlocked the door, held it against her pushing and slipped out sothat, for all her peering, she could see nothing. I looked down on hertolerantly.

"Can't adjust your skates?" I asked again.

"Daddy, I've tried and tried and I just can't turn this old key tightenough."

I continued to look down on her.

"Well, Dad-dee, I can't!"

"Tightly enough."

"What?"

"You can't turn this old key tightly enough."

"That's what I say-yud."

"All right, wench. Sit on this chair."

I got down and shoved one saddle shoe into a skate. It fittedperfectly. I strapped her ankle and pretended to use the key to tightenthe clamp.

Volplas at last. Three of them. Yet I had always been so sure I couldcreate them that I had been calling them volplas for ten years. No,twelve. I glanced across the animal room to where old Nijinsky thrusthis graying head from a cage. I had called them volplas since the dayold Nijinsky's elongated arms and his cousin's lateral skin folds hadgiven me the idea of a flying mutant.

When Nijinsky saw me looking at him, he started a little tarantellaabout his cage. I smiled with nostalgia when the fifth fingers of hishands, four times as long as the others, uncurled as he spun about thecage.

I turned to the fitting of my daughter's other skate.

"Daddy?"

"Yes?"

"Mother says you are eccentric. Is that true?"

"I'll speak to her about it."

"Don't you know?"

"Do you understand the word?"

"No."

I lifted her out of the chair and stood her on her skates. "Tell yourmother that I retaliate. I say she is beautiful."

She skated awkwardly between the rows of cages from which mutants withbrown fur and blue fur, too much and too little fur, enormously longand ridiculously short arms, stared at her with simian, canine orrodent faces. At the door to the outside, she turned perilously andwaved.

Again in the laboratory, I entered the metabolic accelerator andwithdrew the intravenous needles from my first volplas. I carried theirlimp little forms out to a mattress in the lab, two girls and a boy.The accelerator had forced them almost to adulthood in less than amonth. It would be several hours before they would begin to move, tolearn to feed and play, perhaps to learn to fly.

Meanwhile, it was clear that here was no war of dominant mutations.Modulating alleles had smooth