THE CORNISH

RIVIERA

Described by SIDNEY HEATH

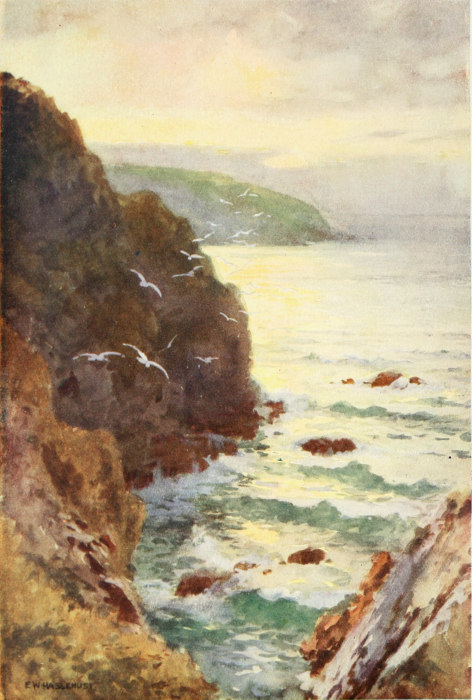

Pictured by E. W. HASLEHUST

BLACKIE AND SON LIMITED

LONDON GLASGOW AND BOMBAY

1915

ENTRANCE TO FOWEY HARBOUR

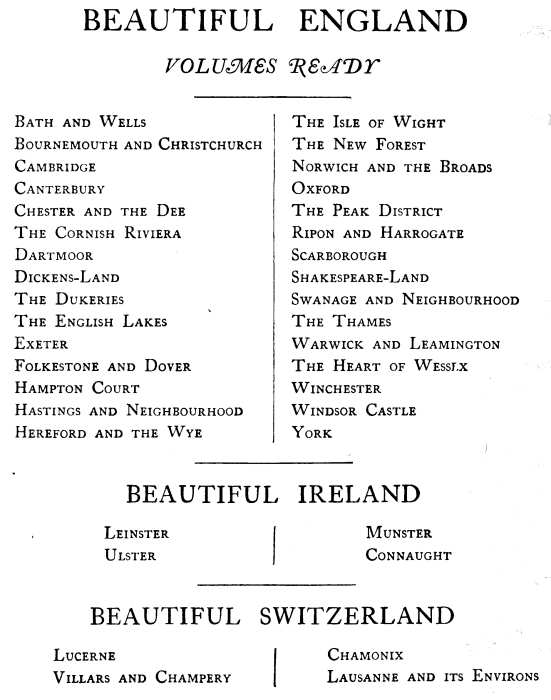

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

PLYMOUTH TO LAND'S END

The majority of our English counties possess some special feature, someparticular attraction which acts as a lodestone for tourists, in theform of a stately cathedral, striking physical beauty, or a wealth ofhistorical or literary associations. There are large districts of ruralEngland that would have remained practically unknown to the multitudehad it not been for their possession of some superb architecturalcreation, or for the fame bestowed upon the district by the makers ofliterature and art. The Bard of Avon was perhaps the unconscious pioneerin the way of providing his native town and county with a valuable assetof this kind. The novels of Scott drew thousands of his[Pg 6] readers to theNorth Country, and those of R. D. Blackmore did the same for the scenesso graphically depicted in Lorna Doone; while Thomas Hardy is probablyresponsible for half the number of tourists who visit Dorset.

Cornwall, on the contrary, is unique, in that, despite its wealth ofCeltic saints, crosses, and holy wells, it does not possess anyoverwhelming attractions in the way of physical beauty (the coast lineexcepted), literary associations, beautiful and fashionable spas, or mediæval cathedrals.

History, legends, folklore, and traditions it has in abundance, whileprobably no portion of south-west England is so rich in memorials of theCeltic era. At the same time one can quite understand how it was that,until comparatively recent years, the Duchy land was visited by fewtourists, as we count them to-day; and why the natives should think andspeak