BEDSIDE MANNER

By WILLIAM MORRISON

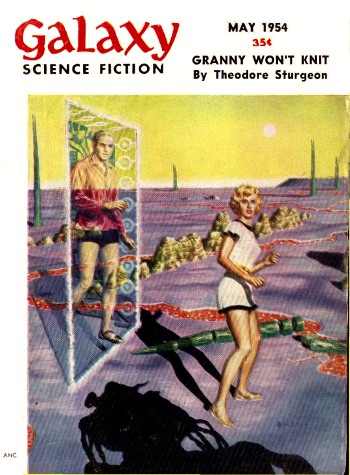

Illustrated by VIDMER

[Transcriber Note: This etext was produced from Galaxy Science FictionMay 1954. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S.copyright on this publication was renewed.]

She awoke, and didn't even wonder where she was.

First there were feelings—a feeling of existence, a sense of stillbeing alive when she should be dead, an awareness of pain that made herbody its playground.

After that, there came a thought. It was a simple thought, and her mindblurted it out before she could stop it: Oh, God, now I won't even beplain any more. I'll be ugly.

The thought sent a wave of panic coursing through her, but she was tootired to experience any emotion for long, and she soon drowsed off.

Later, the second time she awoke, she wondered where she was.

There was no way of telling. Around her all was black and quiet. Theblackness was solid, the quiet absolute. She was aware of painagain—not sharp pain this time, but dull, spread throughout her body.Her legs ached; so did her arms. She tried to lift them, and found toher surprise that they did not respond. She tried to flex her fingers,and failed.

She was paralyzed. She could not move a muscle of her body.

The silence was so complete that it was frightening. Not a whisper ofsound reached her. She had been on a spaceship, but none of a ship'snoises came to her now. Not the creak of an expanding joint, nor theoccasional slap of metal on metal. Not the sound of Fred's voice, noreven the slow rhythm of her own breathing.

It took her a full minute to figure out why, and when she had done soshe did not believe it. But the thought persisted, and soon she knewthat it was true.

The silence was complete because she was deaf.

Another thought: The blackness was so deep because she was blind.

And still another, this time a questioning one: Why, if she could feelpain in her arms and legs, could she not move them? What strange form ofparalysis was this?

She fought against the answer, but slowly, inescapably, it formed in hermind. She was not paralyzed at all. She could not move her arms and legsbecause she had none. The pains she felt were phantom pains, conveyed bythe nerve endings without an external stimulus.

When this thought penetrated, she fainted. Her mind sought inunconsciousness to get as close to death as it could.

When she awoke, it was against her will. She sought desperately to closeher mind against thought and feeling, just as her eyes and ears werealready closed.

But thoughts crept in despite her. Why was she alive? Why hadn't shedied in the crash?

Fred must certainly have been killed. The asteroid had come into viewsuddenly; there had been no chance of avoiding it. It had been a miraclethat she herself had escaped, if escape it could be called—a meresightless, armless and legless torso, with no means of communicationwith the outside world, she was more dead than alive. And she could notbelieve that the miracle had been repeated with Fred.

It was better that way. Fred wouldn't have to look at her andshudder—and he wouldn't have to worry about himself, either. He hadalways been a handsome man, and it would have killed him a second t