I, EXECUTIONER

BY TED WHITE AND TERRY CARR

I am the executioner of the law, terrible

in my majesty. The doomed felon is—myself!

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

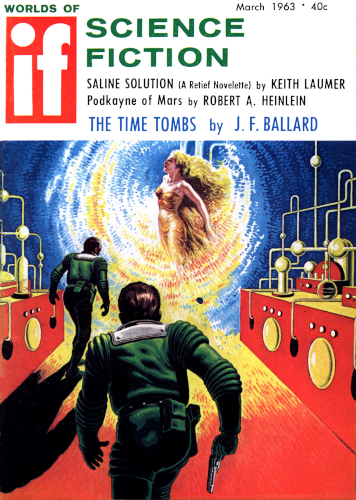

Worlds of If Science Fiction, March 1963.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

I always shook when I came out of the Arena, but this time the tensionwrapped my stomach in painful knots and salty perspiration stung myneck where I had shaved only a little over an hour earlier. And despitethe heavy knot in my stomach. I felt strangely empty.

I had never been able to sort out my reactions to an Execution. Theatmosphere of careful boredom, the strictly business-as-usual airfailed to dull my senses as it did for the others. I could alwaystaste the ozone in the air, mixed with the taste of fear—whethermine, or that of the Condemned, I never knew. My nostrils always gavean involuntary twitch at the confined odors and I felt an almostclaustrophic fear at being packed into the Arena with the other ninehundred ninety-nine Citizens on Execution Duty.

I had been expecting my notice for several months before it finallycame. I hadn't served Execution Duty for nearly two years. Usually ithad figured out to every fourteen months or so on rotation, so I'dbeen ready for it. A little apprehensive—I always am—but ready.

At 9:00 in the morning, still only half awake (I'd purposely sleptuntil the last minute), vaguely trying to remember the dream I'd had,I waited in front of the Arena for the ordeal to begin. The dream hadbeen something about a knife, an operation. But I couldn't rememberwhether I'd been the doctor or the patient.

Our times of arrival had been staggered in our notices, so that a longqueue wouldn't tie up traffic, but as usual the checkers were slow, andwe were backed up a bit.

I didn't like waiting. Somehow I've always felt more exposed on thestreets, although the brain-scanners must be more plentiful in an Arenathan almost anywhere else. It's only logical that they should be. Thescanners are set up to detect unusual patterns of stress in our brainwaves as we pass close to them, and thus to pick out as quickly aspossible those with incipient or developing neuroses or psychoses—thepotential deviates. And where else would such an aberration be aslikely to come out as in the Arena?

I had moved to the front of the short line. I flashed my notificationof duty to the checker, and was waved on in. I found my proper seat onthe aisle in the "T" section. It was a relief to sink into its plushdepths and look the Arena over.

Once this had been a first-run Broadway theater—first a place wheregreat plays were shown, and then later the more degenerate motionpictures. Those had been times of vicarious escape from reality—timeswhen the populace ruled, and yet the masses hid their eyes from theworld. Many things had changed since then, with the coming of regulatedsanity and the achievement of world peace. Gone now were the black artsof forgetfulness, those media which practiced the enticement of theCitizen into irresponsible escape. Now this crowded theater was onlya reminder. And a place of execution for those who would have soughtescape here.

Perhaps thirty people were sitting on the floor of the Arena, whereonce there had been a stage. They sat quietly in chairs not sodifferent from mine, strapped for the moment into a kind of passiveconformity. I looked at them with interest. Strangeness has as muchattra