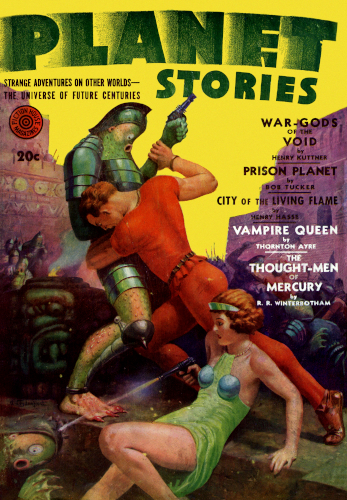

SPACE OASIS

By RAYMOND Z. GALLUN

Space-weary rocketmen dreamed of an

asteroid Earth. But power-mad Norman

Haynes had other plans—and he

spread his control lines in a

doom-net for that oasis in space.

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Planet Stories Fall 1942.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

I found Nick Mavrocordatus scanning the bulletin board at the HaynesShipping Office on Enterprize Asteroid, when I came back with a load ofore from the meteor swarms.

He looked at me with that funny curve on his lips, that might have beencalled a smile, and said, "Hi, Chet," as casually as though we'd seeneach other within the last twenty-four hours.... "Queer laws they gotin the Space Code, eh? The one that insists on the posting of casualtylists, for instance. You'd think the Haynes Company would like to keepsuch things dark."

I didn't say anything for a moment, as my eyes went down those narrow,typed columns on the bulletin board: Joe Tiffany—dead—space armordefect.... Hermann Schmidt and Lan Harool—missing—vicinity ofPallas.... Irvin Davidson—hospitalized—space blindness....

There was a score of names of men I didn't know, in thatspace-blindness column. And beneath, there was a much longer line ofcommon Earth-born and Martian John-Henrys, with the laconic tag addedat the top—hospitalized—mental. Ditto marks saved the trouble ofretyping the tag itself, after each name.

One name caught my eye.

Ted Bradley was listed there. Ted Bradley from St. Louis, my and NickMavrocordatus' home town. It gave me a little jolt, and a momentarylump somewhere under my Adam's Apple. I knew the state Bradley would bein. Not a man any more—no longer keen and sure of himself. A year outhere among the asteroids had changed all that forever.

Shoving from one drifting, meteoric lump to another, in a tiny spaceboat. Chipping at those huge, grey masses with a test hammer thatmakes no sound in the voidal vacuum. Crawling over jagged surfaces,looking for ores of radium and tantalum and carium—stuff fabulouslycostly enough to be worth collecting, for shipment back to theindustries of Earth, at fabulous freight rates, on rocket craft whosepay-load is so small, and where every gram of mass is at premium.

No, Ted Bradley would never be himself again. Like so many others. Itwas an old story. The almost complete lack of gravity, out here amongthe asteroids, had disturbed his nerve-centers, while cosmic raysseeped through his leaded helmet, slowly damaging his brain.

There was more to it than the airlessness, and absence of weight, andthe cosmic rays. There was the utter silence, and the steady stars, andthe blackness between them, and the blackness of the shadows, like thefangs of devils in the blazing sunshine. All of this was harder thanthe soul of any living being.

And on top of all this, there was usually defeat and shattered hope.Not many futures were made among the asteroids by those who dug fortheir living. Prices of things brought from Earth in fragile, costlyspace craft were too high. Moments of freedom and company were toorare, and so, hard-won wealth ran like water.

Ted Bradley was gone from us. Call him a corpse, really. In thehospital here on Enterprize, he was either a raving maniac, orelse—almost worse—he was like a little child, crooning over thewonder of his fingers.

It got me for a second. But then I shrugged. I'd been out here twoyears. An old timer. I