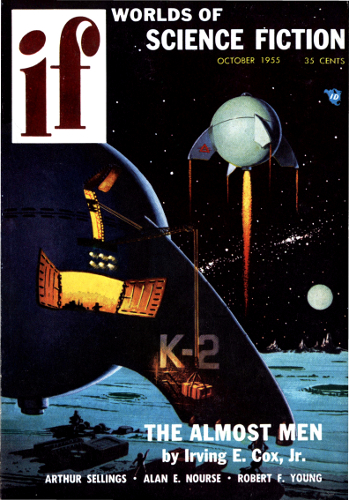

THE ALMOST-MEN

BY IRVING E. COX, JR.

All learning must begin with a need. And

when the tried old ideas won't work for a

people—won't conquer defeat and despair—a

new way of thinking must be found....

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Worlds of If Science Fiction, October 1955.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Hands shook at his shoulder, dragging him awake. Lanny's foster fatherwas bent over him, whispering urgently, "Get up, boy. We have to leave."

Groggily Lanny pushed himself into a sitting position. He had beensleeping in his earth burrow beside Gill, outside Juan's cottage.Hazily Lanny remembered being carried home from the canyon after theexplosion, but he could recall nothing else.

It was an hour before dawn. Gill was dressing; his shoulder was wrappedin a homespun bandage. Lanny got up, staggering a little, and helpedhis brother put on his leather jacket and his weapon belt.

"Thanks, Lan," his brother said.

Lanny touched the bandage. "Shouldn't you heal the cells, Gill?"

"I have to expose it to the sun first. I didn't catch it soon enoughlast night, and too many germs infested the wound." To their fosterfather, Gill added, "I still think you should leave me here. I maynot—"

"You're both my responsibility," Juan Pendillo answered. "We'll survivetogether, Gill, or die together."

"What happened?" Lanny asked as he pulled on his breeches and pushedhis stone knife and his wooden club through the loops of his weaponbelt.

Silently Juan pointed toward the dawn sky. High above them Lanny heardthe whine of a score of enemy police spheres. "They insist on thesurrender of all eight hunters who went out last night."

Gill said, "But Tak Laleen killed Barlow with her energy gun. Why arethey blaming us?"

"Barlow was working for them as a spy," Lanny put in. It was aconvenient explanation, but vaguely he knew he was lying. He felt apang of guilt, but he couldn't understand why. What had he done that heshould be ashamed of?

What had happened last night? Lanny wracked his brain, trying toremember.

Eight hunters had been sent out to bring in a cache of rifles whichLanny's brother, Gill, had found in the rubble of Santa Barbara. Itwas risky business, because under the terms of the surrender treatymen were prohibited the use of all metals in the prison compounds.But the younger generation—boys like Lanny and Gill, born since theinvasion—were more fiercely determined to resist the Almost-men thantheir elders. Armed with fifty rifles, they thought they would bestrong enough to attack the Chapel of the Triangle.

The Almost-men: the children had coined the word, subtly assertingthe pride of man. Yet they knew it was a semantic trick they playedupon themselves. It changed nothing. The conquerors were physicallyidentical to men; their enormous superiority was entirely technological.

As the eight hunters crept toward the ruins of Santa Barbara, through anarrow canyon, old man Barlow suddenly emerged from the brush and stoodgrinning at them. It was his privilege to join the hunters; any citizenof the settlement could have done so. But the younger generation hatedBarlow. He was the practical man; he called himself a realist. He neverallowed them to forget they were defeated, imprisoned and withoutweapons; he took savage delight in poking holes in their plans forresistance.

"What are you doing here?" Lanny's