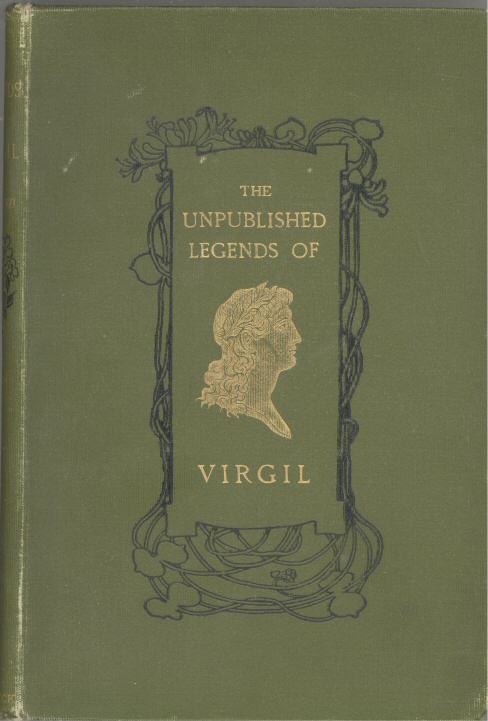

Transcribed from the 1899 Elliot Stock edition ,

THE

UNPUBLISHED LEGENDS

OF

VIRGIL.

COLLECTEDBY

CHARLES GODFREY LELAND.

LONDON:

ELLIOT STOCK, 62, PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C.

1899.

p. vTOTHE

SENATOR AND PROFESSOR

DOMENICO COMPARETTI,

AUTHOROF

“VIRGIL IN THE MIDDLEAGES,”

THIS WORK ISDEDICATED

BY

CHARLES GODFREY LELAND

Florence, September,1899.

p.viiPREFACE.

All classic scholars are familiar with the Legends of Virgilin the Middle Ages, in which the poet appears as a magician, thelast and best collection of these being that which forms thesecond volume of “Virgilio nel Medio Aevo,” bySenator Professor Domenico Comparetti. But havingconjectured that Dante must have made Virgil familiar to thepeople, and that many legends or traditions still remained to becollected, I applied myself to this task, with the result that indue time I gathered, or had gathered for me, about one hundredtales, of which only three or four had a plot in common with theold Neapolitan Virgilian stories, and even these containedoriginal and very curious additional lore. One half ofthese traditions will be found in this work.

As these were nearly all taken down by a fortune-teller orwitch among her kind—she being singularly well qualified byyears of practice in finding and recording such reconditelore—they very naturally contain much more that is occult,strange and heathen, than can be found in the other tales. Thus, wherever there is opportunity, magical ceremonies aredescribed and incantations given; in fact, the story is oftenonly a mere frame, as it were, in which the picture or truesubject is a lesson in sorcery.

But what is most remarkable and interesting in thesetraditions, as I have often had occasion to remark, is the p. viiifact thatthey embody a vast amount of old Etrusco-Roman minor mythology ofthe kind chronicled by Ovid, and incidentally touched on orquoted here and there by gossiping Latin writers, yet of which norecord was ever made. I am sincerely persuaded that therewas an immense repertory of this fairy, goblin, or witch religionbelieved in by the Roman people which was never written down, butof which a great deal was preserved by sorcerers, who are mostlyat the same time story-tellers among themselves, and of this muchmay be found in this work. And I think no critic, howeverinclined to doubt he may be, will deny that there is in the oldmythologists collateral evidence to prove what I haveasserted.

It may be observed that in these Northern legends, Virgil isin most cases spoken of as a poet as well as magician, but thathe is before all, benevolent and genial, a great sage invariablydoing good, while always inspired with humour. Mr. RobinsonEllis has shrewdly observed that, in reading the Neapolitan talesof Virgil, “we are painfully struck with the absence, forthe most part, of any i