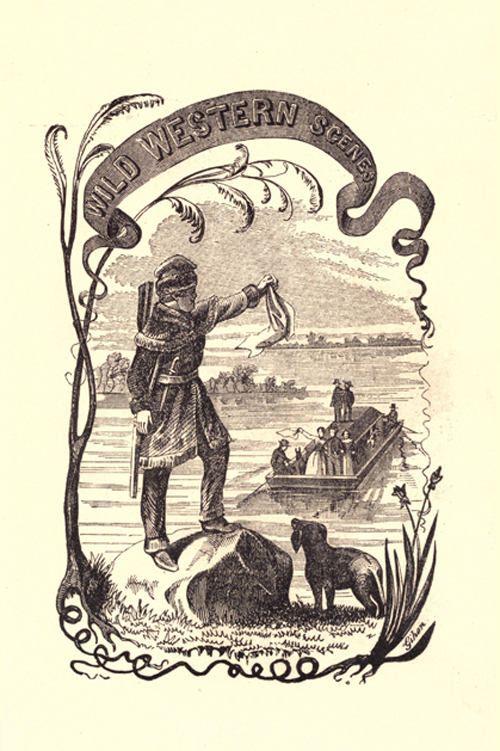

WILD WESTERN SCENES:

A NARRATIVE OF ADVENTURES IN THE WESTERN WILDERNESS,

WHEREIN

THE EXPLOITS OF DANIEL BOONE, THE GREAT AMERICAN PIONEER ARE PARTICULARLY DESCRIBED

ALSO,

ACCOUNTS OF BEAR, DEER, AND BUFFALO HUNTS—DESPERATE CONFLICTS WITH THE SAVAGES—WOLF HUNTS—FISHING AND FOWLING ADVENTURES—ENCOUNTERS WITH SERPENTS, ETC.

New Stereotype Edition, Altered, Revised, and Corrected

By

J.B. JONES.

Author of "The War Path," "Adventures of a Country Merchant," etc.

Illustrated with Sixteen Engravings from Original Designs

Philadelphia:

J.B. Lippincott & Co.

1875

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1856, by J.B. Jones,

in the Clerk's Office of the District Court

for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania.

Stereotyped By L. Johnson & Co.,

Philadelphia.

PREFACE.

When a work of fiction has reached its fortieth edition, one would suppose theauthor might congratulate himself upon having contributed something of animperishable character to the literature of the country. But no suchpretensions are asserted for this production, now in its fortieth thousand.Being the first essay of an impetuous youth in a field where giants even havenot always successfully contended, it would be a rash assumption to suppose itcould receive from those who confer such honors any high award of merit. It hasbeen before the public some fifteen years, and has never been reviewed. Perhapsthe forbearance of those who wield the cerebral scalpels may not be furtherprolonged, and the book remains amenable to the judgment they may be pleased topronounce.

To that portion of the public who have read with approbation so many thousandsof his book, the author may speak with greater confidence. To this class of hisfriends he may make disclosures and confessions pertaining to the secrethistory of the “Wild Western Scenes,” without the hazard ofincurring their displeasure.

Like the hero of his book, the author had his vicissitudes in boyhood, andcommitted such indiscretions as were incident to one of his years andcircumstances, but nevertheless only such as might be readily pardoned by thecharitable. Like Glenn, he submitted to a voluntary exile in the wilds ofMissouri. Hence the description of scenery is a true picture, and severalcharacters in the scenes were real persons. Many of the occurrences actuallytranspired in his presence, or had been enacted in the vicinity at no remoteperiod; and the dream of the hero—his visit to the hauntedisland—was truly a dream of the author’s.

But the worst miseries of the author were felt when his work was completed; hecould get no publisher to examine it. He then purchased an interest in a weeklynewspaper, in the columns of which it appeared in consecutive chapters. Thesubscribers were pleased with it, and desired to possess it in a volume; butstill no publisher would undertake it,—the author had no reputation inthe literary world. He offered it for fifty dollars, but could find nopurchaser at any price. Believing the British booksellers more accommodating, afriend was employed to make a fair copy in manuscript, at a certain number ofcents per hundred words. The work was sent to a British publisher, with whom itremained many months, but was returned, accompanied by a note declining totreat for it.

Undeterred by the rebuffs of two worlds, the author had his cherishedproduction published on his own account, and was remunerated by the sale of thewhole editio